Modi praised for climate reforms then upset Glasgow Pact

Suggestions that China led India into negative stance

With hindsight, no-one should have been surprised when India unexpectedly insisted at the end of the COP26 negotiations last weekend that the Glasgow Climate Pact should only call for coal power to be “phased down” not “phased out”, thus upsetting a text that the organisers innocently assumed was agreed with universal support from nearly 200 countries.

Coal is so central to India’s economic, social and political life that, realistically, it was unthinkable for it to have agreed to phase it out. It is currently offering 40 new mines to private sector companies – on forest land that will be destroyed – and is increasing imports,

Not only does coal fuel 70% of India’s power generation and employ millions of people directly and indirectly, it also enriches the frequently graft-based political-business nexus. Top private sector companies such as the Adani group, which is close to prime minister Narendra Modi, operate as major importers as well as having a growing role in the country’s vast and environmentally-damaging opencast mines.

Blindsided

Leaders of other countries and the conference organisers seem to have been blindsided by Narendra Modi’s appearance at the start of the summit where he sounded a committed and balanced advocate of climate action, even though his date for net zero emissions was 2070, not the 2050 pledged by the UK, US and other high-income countries, nor 2060 chosen by China, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

Even my old newspaper the Financial Times, usually an unrelenting Modi critic, ran an editorial on November 2 saying that it “was encouraging and a vital step in limiting global warming” for the world’s third-biggest emitter and most populous country to have set a target to reduce its emissions to virtually zero.

India is the biggest producer and user of coal after China, but it is currently suffering from serious shortages because of inefficient mining and mismanagement of supplies, plus a post-pandemic surge in demand. Prices are rising, so it would have been politically highly risky the government to agree to phasing the fossil fuel out. “If the government had done that in Glasgow, and Delhi and Mumbai had shut down because there was no coal to run power plants, how would that have played out politically?”, one analyst asked me rhetorically.

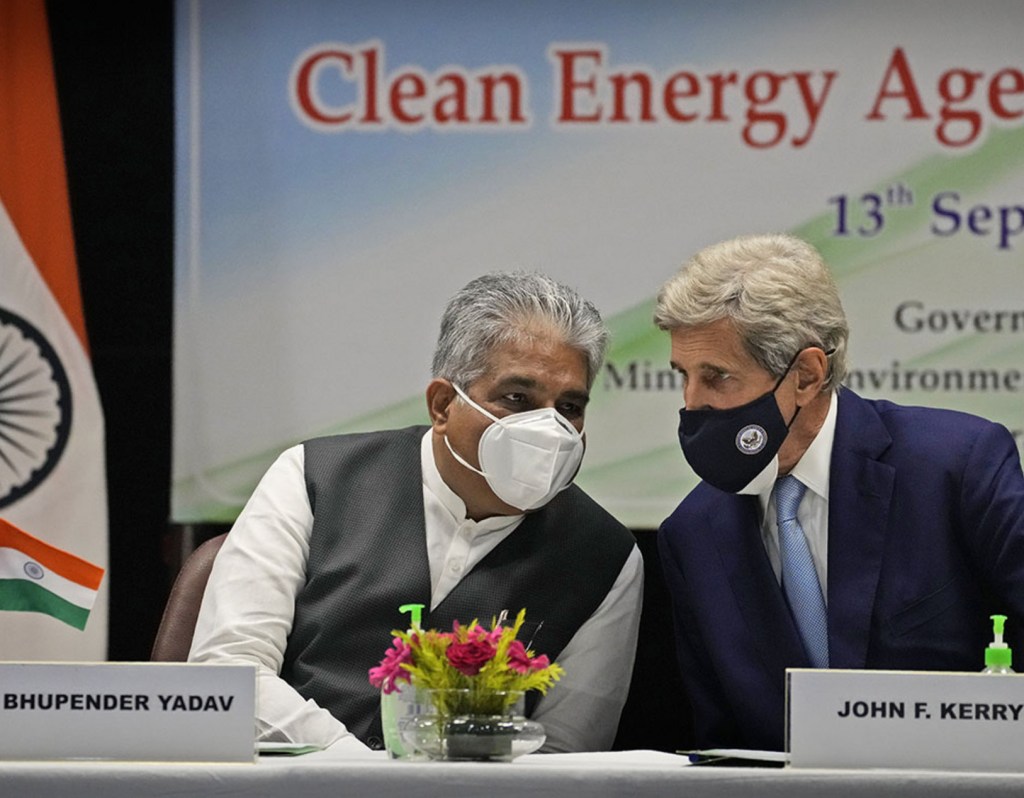

There is also a suggestion that India was conned into insisting on phasing down by China; a move that might have appealed to Modi at a time when the two countries have had an 18-month long military confrontation on their Himalayan border. Indian government sources in New Delhi are now briefing journalists that India should not be blamed for the change, and Bhupendra Yadav the environment minister, spoke about it later (Nov 20).

“A perennial problem in Indian efforts at COPs in the past has been its tendency to provide cover for China,” according to the Business Standard, a leading Indian newspaper. “New Delhi allowed itself [in Glasgow] to play the bad guy and willy-nilly defend Beijing’s policy choices”.

India’s initiatives

Modi was taking an important step when he proposed the 2070 target because he was abandoning India’s previous pose of grumbling about developed countries while refusing to stake out its own contribution. The 2070 initiative reversed the established line of refusing to name a date and was apparently decided in his prime minister’s office without even the environment ministry knowing what was planned.

India is also committed, as Modi said in Glasgow, to obtaining 50% of India’s electric power from non-fossil energy resources by 2030 (building 450 gigawatts of solar and other renewable capacity) and, by the same year, reducing the carbon emissions’ intensity of the economy by 45% from the 2005 level. But it appears not to have signed a zero deforestation commitment.

It is not clear when Modi decided on the coal move – possibly it was not till after he had returned to Delhi, and maybe felt the heat from private sector miners and realised the political risks during coal shortages and the need for increased imports.

This was the first time that coal had been mentioned in a COP agreement and early drafts of the Glasgow Pact contained an commitment to phase out unabated coal (unabated means coal that is burned without emission-reducing carbon capture and storage technology).

Modi left the job of announcing the unpopular move of overturning what was to have been the final draft to Bhupendra Yadav, who should not have been under-estimated by other countries – he has a reputation as a shrewd lawyer and has written a book on environmental legislation.

China intervened

China seems to have intervened first, indicating it was prepared to de-rail the proposed pact. It argued that demands on countries to meet the primary average global temperature rise to 1.5 deg C. should be adjustable according to their need to eradicate poverty. India agreed with this and moved into the lead, with Yadav announcing the demand for a redraft in a plenary session last Saturday.

India and China are now being widely criticised for the disruption, though they would argue that, while they are among the biggest coal polluters, Australia and South Korea lead on a per capita basis. India’s per capita emission from coal power is considerably less than the global average.

Coal is mostly mined inefficiently by Coal India, a monopoly-oriented public sector corporation that has for decades resisted modernisation and accounts for some 80% of supplies. Most of the remaining 20% comes from Australia, Indonesia and South Africa, making India the world’s biggest importer.

Economic reforms have for years pushed for coal mining to be opened to the private sector. After a hiatus a decade ago caused by mining licences being corruptly awarded without open tendering, some 40 mines are now being operated by companies for their power and steel plants.

This is now being expanded with the private sector tendering for 40 new mines with another 40 to follow later, involving a total of 55 billion tonnes of coal that can be sold on the market. Many of the mines are located on long-protected forest land which will be destroyed, along with habitats for local people.

This brings increased worries about environmental laws and regulations being broken or ignored because of the political clout of private sector companies that can stretch from the prime minister’s office down to environmental and other local government officials.

Lack of leadership

Part of the problem throughout the preparations for COP26 was a lack of British leadership. Alok Sharma, the COP president and a former Conservative government minister, has been admired for his stoicism but he is not enough of a political figure to break deadlocks.

That would have been fine if Boris Johnson had been fully focussed, but he has a short attention span and his lack of involvement was illustrated when he went on a Costa del Sol holiday a week before the Glasgow events began instead of lobbying internationally for a positive outcome.

John Kerry, the US climate envoy admitted as the events closed that he had not expected problems. “Did I appreciate we had to adjust one thing tonight in a very unusual way? No. But if we hadn’t done that we wouldn’t have a deal. I’ll take phase it down and take the fight into next year,” he said.

This article is on the Asia Sentinel news website https://www.asiasentinel.com

You make some very valid points, John, particularly about the fullness of the pre-Cop preparation work, or lack of it, that was needed. This indeed failed to appreciate the adjustment difficulties that the GOI would be faced with in order to conform to a new order.

China’s position is different. China indeed has to, and will, in pursuit of a strong centrally directed policy redevelop and reorientate its smokestack regions. It will want to show to the rest of the world that it will become the leader in green, clean, technology but this will take time and from a Chinese point of view it has to be their timetable and not one set by the West. That it will succeed is more than likely given how it has achieved all kinds of challenging goals over the past 40 years.

It suited therefore both India and China to modify the results arising from the agenda that Kerry, Sharma and the Western leaders had hoped for.

At least Cop26 is a start but greater understanding by Western leaders of others needs to be improved.

By: William Knight on November 18, 2021

at 5:27 pm