Modi refuses to have India join either camp in a ”polarised” world

A balancing act that takes China and regional tensions into account

India is beginning to shift its position on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – and resist pressure from Moscow – as the full horrors of the devastation and human cruelty become daily more evident.

It has not joined the US, Europe, and other Western powers in voting against Russia at the United Nations where it has abstained eleven times since the invasion began, the latest being on April 7 when Russia was suspended from the UN Human Rights Council.

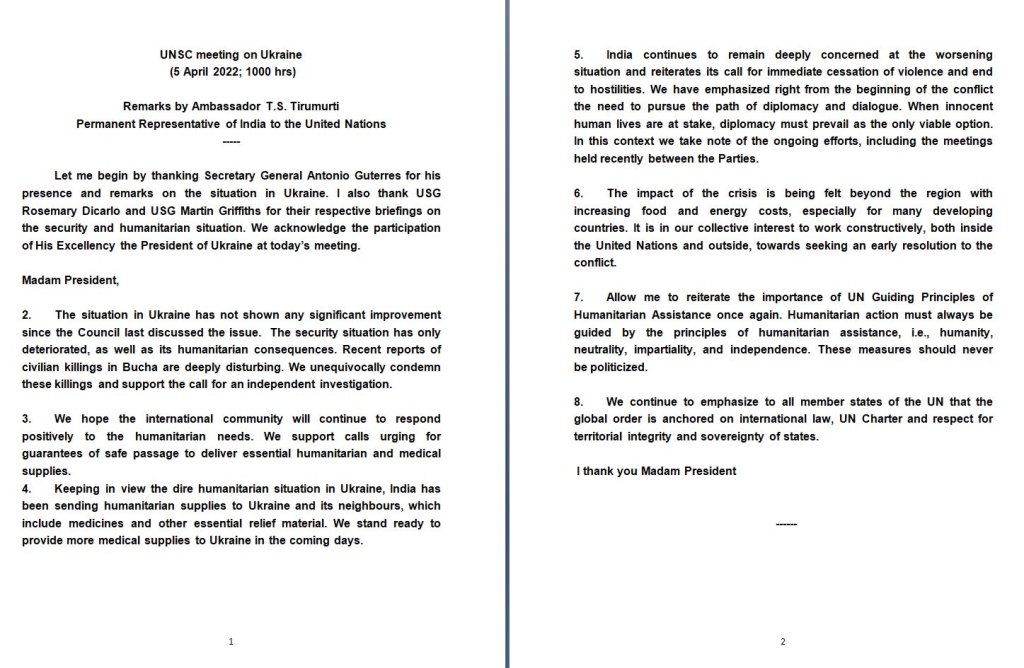

But it did not respond to pressure from Russia which reportedly warned that abstention on the Human Rights Council vote would be viewed as an “unfriendly gesture”. Earlier, on April 5, it stepped up its criticism at a Security Council meeting when it condemned the killing of civilians (below) and called for a full independent investigation.

These are the latest stages of the balancing act that India has adopted since the beginning of the invasion. It wants to avoid upsetting its old ally and current trading partner while maintaining its growing relationship with the US.

India knows that its stance is being watched by Beijing, which has been growing closer to Russia and appears to be easing tensions on the currently militarised Himalayan border. At the same time, governments in both Pakistan and Sri Lanka, where China exerts considerable influence, are in crises.

Against that background, it looks as if India’s response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine will be driven by horror at the destruction and killings, rather than by incessant lobbying from the US, the UK and European countries.

The lobbying has led to India almost restating its old non-aligned foreign policy. Speaking at a Bharatiya Janata Party rally on April 6, prime minister Narendra Modi referred to the global pressure on India to take a stronger stand against the invasion and said that, in a polarised world, the country had stood firm on its policy and had prioritised national interest. Though he did not spell it out, that meant not siding with the US and the West.

“Expecting New Delhi to take a more strident official position against Moscow is unrealistic, and Western criticism and pressure will probably rankle a postcolonial society like India’s,” says Shivshankar Menon, a former top diplomat and national security adviser.

UN statement

“Recent reports of civilian killings in Bucha are deeply disturbing,” T.S. Tirumurti, India’s permanent representative to the UN, told the Security Council where it currently has a seat as a non-permanent member. “We unequivocally condemn these killings and support the call for an independent investigation”.

Tirumurti was speaking shortly after US secretary of state Antony Blinken talked by phone with India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, in advance of meetings they are due to hold, along with their defence ministers, in Washington next week.

A similar line was taken in the UN by China which, along with India and other nations (notably in Africa and South Asia), has abstained on UN resolutions condemning Russia.

India is still anchored to its historic relationship with Russia that goes back to the years of the Soviet Union. It is heavily reliant on Russia for defence, oil and other supplies, as I explained here on February 28.

There is also an underlying – and easily awakened – public antipathy to the US and to former colonial powers that has been exacerbated by persistent and sometimes insensitive American lobbying.

There seems to be an assumption in the US and Europe that, as the world’s largest democracy, India should have taken the same line as western democracies from the beginning of the Russian invasion.

The US is however widely regarded in India as a fair-weather friend that currently finds the country useful in resisting China’s Asian ambitions. There is a strong opinion-forming liberal elite that abhors what Russia is doing. That is however offset by general antipathy for the US, which is most strongly felt by the Hindu-nationalist right wing as well as by opinion formers on the leftist end of the political spectrum. Narendra Modi, the prime minister, does not follow either extreme line, and has been working to strengthen ties with the US while maintaining Russia relations.

The Washington Post summed up the trend on March 29, when it reported that popular Indian television channels have been persisting with the lines that “the United States provoked Russia into attacking Ukraine. The Americans were possibly developing biological weapons in Ukraine. Joe Biden, the U.S. president who fumbled the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, has no business criticizing India over the war he sparked in Ukraine.”

Daleep Singh, America’s deputy national security adviser, had an unproductive official visit to New Delhi last week when he warned that there “are consequences to countries that actively attempt to circumvent or backfill sanctions”.

Russia and India are openly reviving their old Soviet Union era rupee-rouble trade arrangements to bypass sanctions, and the Bank of Russia and the Reserve Bank of India are looking for additional ways to organise payments.

That prompted Singh, who heads the US sanctions strategy, to say, “We are very keen for all countries, especially our allies and partners, not to create mechanisms that prop up the [Russian] rouble”

The implied threats, which smacked of an earlier more tetchy era in India-US relations, were quickly criticised.

Syed Akbaruddin, India’s former UN ambassador, tweeted that Singh had shown “a display of rather crude public diplomacy of a nature that is not expected from a friendly country like the US”. Akbaruddin was Modi’s trusted foreign affairs spokesman before going to the UN, which adds weight to his sharp remarks.

Delhi has been deluged with top level foreign government visitors in recent weeks including Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov and the British foreign secretary Liz Truss, who had a public seminar session with Jaishankar.

Truss was careful not to bully or issue threats, but made it clear that she thought democracies should stand together against Russia. Jaishankar took the line that countries should respect each other’s priorities, and gently mocked Europe for its increasing gas purchases while stating that India would have significantly reduced its dependence on Russian oil by the end of the year.

Deaf dialogue

Their conversation, while calm and firmly based on how to develop the two countries’ close relationship, was a dialogue of the deaf on Russia and Ukraine.

“If India has chosen a side, it is a side of peace and it is for an immediate end to violence,” Jaishankar told parliament on April 6. That had been India’s “principled stand” in international forums and debates.

Answering criticisms that India usually stands on the sidelines during international crises, Jaishankar added it continued “to push for dialogue” and an end to violence. “If India can be of any assistance in this matter, we will be glad to contribute,” he said.

Both Modi and Jaishankar have now spelt out India’s answer to the stream of visitors trying to turn them against Russia – India is not joining their camp and will adjust its approach as it sees fit. That is not of course the answer that Biden and other western world leaders wanted to hear.

Great read. And the NAM. Nehru! Warm regards

On Thu, Apr 7, 2022 at 3:31 AM Riding the Elephant wrote:

> John Elliott posted: ” Modi refuses to have India join either camp in a > ”polarised” world A balancing act that takes China and regional tensions > into account India is beginning to shift its position on Russia’s invasion > of Ukraine as the full horrors of the devastation a” >

By: Jyotirmoy Chaudhuri on April 8, 2022

at 8:36 am