A tribute to India’s “most misunderstood prime minister”

Written by “the last Pakistani left in India”

With Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party virtually certain to win India’s general election for the third consecutive time in May, the decline of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty and its domination of the once all-powerful Congress party will inevitably hit headlines, as it has repeatedly done for years.

So it’s running against the tide for two books to appear now supporting the reputation of Rajiv Gandhi, the most unsung of the dynasty’s three prime ministers. Maybe that is not surprising though, given the style of the author. Mani Shankar Aiyar, a diplomat turned voluble maverick and contrarian politician, is a rare but committed defender of Gandhi, having worked closely with him when he was prime minister from 1984 to 1989, and then in opposition for 18 months till he was assassinated in 1991.

No-one who knows Mani and has heard him speak, at length, will be surprised that he has spun these substantial volumes with a third on the way. The books are highly readable, laced with occasional jibes and often irreverent anecdotes.

He describes a prominent Delhi journalist (now a columnist) as “she of the quill dipped in hemlock”. An American lady diplomat in prohibition-bound Pakistan invited him to her room for an illicit late-evening drink saying, “They’ll all be thinking we’re up to the other thing and we can just quietly have a nightcap!’ Aiyar comments: “I should perhaps have penned my first DIY book: ‘How to Live with Prohibition – and Learn to Love It!”

The books are notable not just for such snippets and the Gandhi focus, but also the history of Aiyar’s own life. That includes going, like Gandhi, to Cambridge after the elite Doon School in north India which, he says, “brought me up to be a good little Englishman”

There is also for an unfashionable affection for India’s troublesome neighbour Pakistan. A book review there has dubbed him “the last Pakistani left in India”, reflecting his fondness – for the people – that began in Karachi where he re-opened the Indian Consulate in December 1978 and stayed for four years. Since then, Aiyar has been a constant promoter of peace between the two nuclear powers.

What is striking in the books is that they give fascinating historical insights into issues and crises experienced by Aiyar that are still active today.

Most immediate is Gandhi’s apparent decision to allow the gates of the long-closed Babri Masjid mosque in Ayodhya, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, to be re-opened. That led to its demolition by Hindu protestors and eventually to a BJP campaign to build a new grand temple on what was an old Hindu site. On January 22, Modi will preside at a ceremony marking the inauguration of the under-construction temple. Also topical is Gandhi’s much criticised endorsement (in what was known as the Shah Bano case) of Muslim Personal Law on women’s limited divorce settlement rights. This would be corrected under the Modi government’s proposed controversial Uniform Civil Code.

Other issues range from the 1980s Sikh demand for an independent state called Khalistan that has recently surfaced in a diplomatic row with Canada, to a Swedish Bofors gun corruption scandal that enveloped Gandhi and still has echoes in alleged high level graft on foreign defence deals.

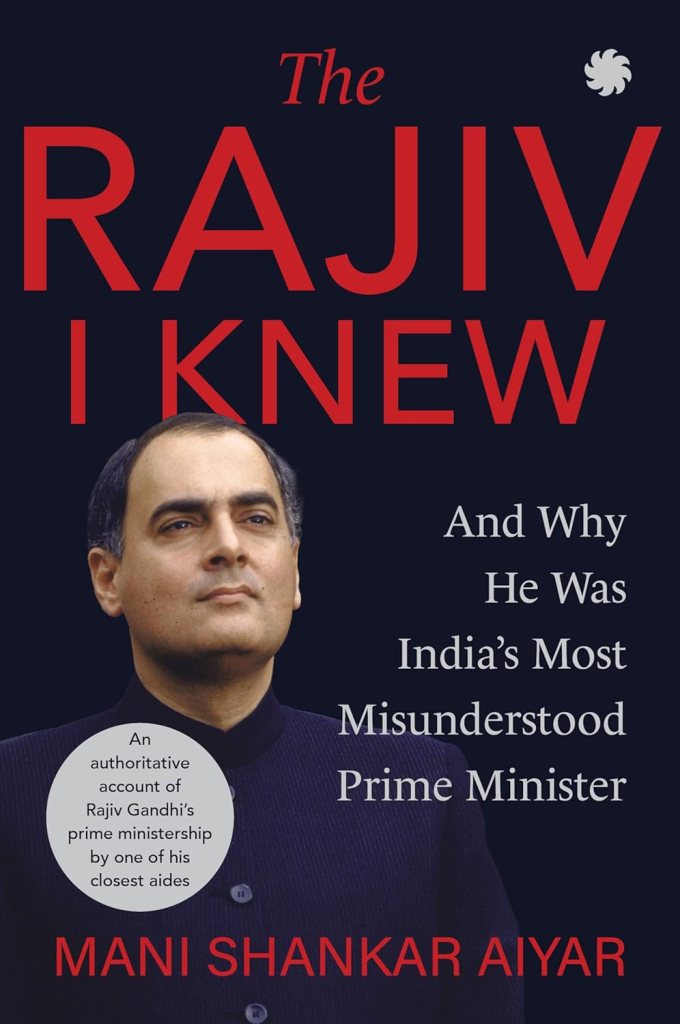

The first of the books, Memoirs of a Maverick – The First Fifty Years, is Aiyar’s own autobiography and was published in August. It includes a long section on Gandhi’s time in office, which has been expanded in some detail in his second book that is out this month. Called The Rajiv I Knew and Why he was India’s Most Misunderstood Prime Minister, it goes into more detail on what Aiyar calls a “political biography” about Gandhi’s record both in power and in opposition.

A third volume, now being edited, covers Aiyar’s 21 years in parliament, five as a hard working cabinet minister (including petroleum & natural gas and youth affairs & sport). It then goes on to what he describes as his “marginalisation in the [Congress] party since 2010” – something that he feels deeply.

That marginalisation was a waste of a talent that Aiyar displayed as petroleum minister. As I reported (much to his surprise) in The Economist in 2005, he transformed “a government department better known for the illicit allocation of petrol-pump licences to politicians’ families and friends into a significant player on the international stage”. He promoted an Asian gas grid and began moves to bring natural gas to India from Iran, Myanmar and Turkmenistan.

Aiyar argues that Gandhi’s “principal legacy to the nation was the constitutional imperative of Panchayati Raj that would by now have blossomed had he remained at the helm of the nation for a few more decades”. Aiyar made this system of village self-government a personal crusade and at one point had ministerial responsibility for its development.

Economic reforms

The books deservedly give Gandhi credit for initiatives he launched, challenging widespread criticism on economic controls that helped to pave the way for major reforms launched by a later Congress government in 1991. The imagination of India’s educated youth was captured for what could be achieved and interest was boosted in stock markets.

On foreign policy, Gandhi developed relations with China, took mis-steps in Sri Lanka over Tamil separatism, but worked well with the Pakistan’s military dictator-president Zia ul-Haq and then with Benazir Bhutto when she became prime minister. If Gandhi and Bhutto had lived and stayed in power, more could maybe have been achieved.

Gandhi had many critics and opponents who tried to scupper his well-meaning initiatives and Aiyar picks out one prime villain – cousin Arun Nehru, a politician who he describes as “rough, brusque, dominating and a bully”.

Nehru ensured that Gandhi became prime minister within hours of his mother Indira Gandhi being assassinated (by Sikh security guards) in 1984. At the time it seemed that Nehru’s aim was keep the family in power, but Aiyar suggests his real purpose was to increase his own power by dominating the apparently (but not always) mild Gandhi. Aiyar accuses Nehru of playing a central role in organising the bribes that led to the Bofors scandal and also for his role in unlocking the Babri Masjid gates and the Shah Bano case.

The thesis is that Gandhi had faults and made mistakes, some naive and some where he was misled by advisers. I was the Financial Times‘ correspondent in Delhi during most of the years Gandhi was in power. Perhaps inevitably, Aiyar sometimes overstates his case but I agree with him that Gandhi’s intentions were good, and that he left the legacy of a country ready for the major 1991 economic reforms, paving the way for what India is achieving today. That is important at a time when it is rare to hear positive comments on the fading dynasty’s contribution to the country’s development.

Memoirs of a Maverick – The First Fifty Years (1941-1991) By Mani Shankar Aiyar JUGGERNAUT Delhi Kindle and paperback

The Rajiv I Knew and Why he was India’s Most Misunderstood Prime Minister by Mani Shankar Aiyar, JUGGERNAUT Delhi, Kindle and paperback

Many thanks John , for drawing attention to the two books . I have long been an admirer of Mani Shankar Aiyar and will look forward to reading the books .

By: Saiful Haque on January 14, 2024

at 2:23 pm