This is an extended version of an article titled “Modi, Good or Bad” that was commissioned in December 2024 by “The Round Table Journal of Commonwealth and International Affairs and Policy Studies” (where I am an Editorial Board member). It has just been published on-line in the February issue as part of a special South Asia section.

The balance between driving the country forward….

.…and Hindu nationalism’s impact on a range of freedoms

Will history look back on Narendra Modi’s years as prime minister of India as a time when the country was launched into a proud and successful nationalist future? Or will it be seen as a time when the bedrock of India’s secular democracy was riven by Hindu nationalism and by challenges to its essential institutions?

Discussing this involves a far more detached assessment than is usual in much of the debate on Modi’s rule, which needs to be seen in its immediate historical setting.

Modi’s national political emergence filled leadership vacuums, first in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) when he became the party’s prime ministerial candidate in 2013, and then in the country when he won the 2014 general election. Effective leadership had been collapsing in the Indian National Congress government, where Sonia Gandhi was the power behind the prime minister, Manmohan Singh, and her dynastic heir-apparent son, Rahul.

Economic reforms begun under an earlier Congress government in 1991 had lost momentum.

For too long, the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty and its fellow elite had focussed on protecting the thousands of millions of poor with what were often corruptly administered welfarism sops and support programmes. What they had not provided was real hope of a better future with jobs and improvements in basic services such as houses, electricity, gas, health and other services.

Modi filled that policy vacuum when he swept to power in 2014 with the promise of a better future for all including economic growth and development. Since then, he has dominated Indian politics and there seems little prospect of him abiding by the BJP’s retiring age of 75 (which he introduced to remove one or two party elders) on his birthday in September.

His principal political aim has been to build a stronger India and ensure continued rule by the BJP. That includes eclipsing the India National Congress’s Nehru-Gandhi dynasty from the country’s story since independence so that he replaces Jawaharlal Nehru as the greatest prime minister.

At the same time, Modi’s significantly more controversial ideological aim has been to restore India to the perceived Hindu supremacy that existed before it was conquered and colonised by Muslim Mughal and Christian British invaders. In this scenario, India is seen to have now resumed the path of its historical destiny as a Hindu nation, which was left behind when Nehru and Congress adopted tolerant all-religion secularism after independence. That decision followed intense debate among the country’s leaders about the direction in which the Hindu-majority country should go after Pakistan became a separate Muslim nation. Modi’s and the BJP’s current approach is therefore embedded in the Hindu nationalist historical line.

Modi is a polarising figure abroad as well as at home, but he has successfully promoted India internationally as a growing world economy open for investment, and as a leading member of international alliances such as the G-20 and BRICS. No longer does the country punch below its weight, which it did for decades.

He has established strong (and heavily publicised) relationships with world leaders, especially but not only with President Donald Trump – a connection now reaping some benefits for India. Such high profile signs of importance boost Modi’s political image back in India and enable him to tie the widespread Hindu diaspora into his political fold.

Modi’s critics rarely acknowledge his plus points. Occasionally, however, there is recognition, as Ramachandra Guha, a historian and prominent social commentator, showed in a critical Foreign Affairs essay headed India’s Feet of Clay, published just before the 2024 general election:

“Although his [Modi’s] economic record is mixed, he has still won the trust of many poor people by supplying food and cooking gas at highly subsidised rates via schemes branded as Modi’s personal gifts to them. He has taken quickly to digital technologies, which have enabled the direct provision of welfare and the reduction of intermediary corruption. He has also presided over substantial progress in infrastructure development, with spanking new highways and airports seen as evidence of a rising India on the march under Modi’s leadership.”

The key point here is that Modi has introduced and implemented far more effective initiatives for the poor than previous Congress governments that were weak on implementation. That has transformed lives with improved services, especially in deprived areas. Low-income families have been provided with funds to build ‘pucca’ (permanent) homes to replace or extend traditional rural and slum dwellings.

Modi’s Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Mission) programme has improved sanitation by building tens of millions of toilets for the poor. There has also been provision of gas cylinders, electrical connections and more than 500 million bank accounts. On a broader front, there are the highways that Guha mentioned and a mass of other infrastructure schemes.

Inevitably, implementation has been far from perfect. Toilets have lacked water or drainage and many are not in use. Concrete homes are often inadequate in ultra hot weather, while gas and electricity supplies are unreliable. There has been inevitable corruption as well as poor delivery, but Modi is credited for bringing hope, and for at least doing far more than previous governments.

On the macro-economic level, there have been significant reforms since 2014, some of which had been initiated with less follow-through by Congress governments. Regulations for big business have been dramatically eased (but not sufficiently to meet what is needed to drive sustained growth); and India is now regarded internationally as a desirable though difficult investment location at a time when companies are seeking alternatives to China.

Corruption however is still rife at all levels throughout India and continue to be a serious issue, despite Modi claiming to the contrary. The government’s appetite for reforms seems to have faded and lost drive after the 2024 general election that drastically reduced the number of the BJP’s parliamentary seats. Economic growth at around 6% is laudable, but not sufficient to reach Modi’s target of India being a developed economy by the 2047 centenary of independence.

‘Truly’ Indian Hindus

Religion plays a major role in the country – over 80% of Indian adults “consider religion is very important in their life” and 60% pray daily, according to a 2019-20 survey report by the respected US-based Pew Research Centre. Nearly two-thirds of Hindus (64%) said it was very important to follow their religion to be “truly” Indian, so it is not surprising that Modi finds it easy to link religion with nationalism and the BJP.

With its young and aspirational population, the country has seemed ready for the past decade to respond to the nationalist approach. For many in India’s upper classes, Modi has generated a feeling of self-worth and national pride, while the aspirational middle classes see chances of advancement in an increasingly strong nation. For the poor, he remains a paternal figure and for everyone he has provided national stability at a time of traumatic change in most neighbouring countries, compounded now by the Trump presidency.

That nationalism and re-injection of national pride does not need however to go anywhere near the current authoritarian extremes of Hindu majoritarianism where Muslims and other minorities (including Christians in some areas) feel persecuted and vulnerable second-class citizens. That is prevalent in BJP controlled states such as Uttar Pradesh, but is far less evident in the south. The Pew research found most respondents said it was important to respect all religions, which indicates that there are limits to how stridently Hindutva can be pushed.

Many Hindus however do harbour anti-Muslim sentiments. In the past, such views were mostly suppressed, or self-censored, but they are now aired increasingly openly, sometimes viciously against those who disagree.

As a reviewer of a recent powerful book The Identity Project: The Unmaking of a Democracy wrote about the impact on normal social or family life, many people have “had to mute family or school WhatsApp groups or even exit them, unable to stand the poison unleashed against minorities. Family ties have been soured in this othering project.”

The Hindu nationalist (Hindutva) doctrine stems from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the umbrella organisation that embraces the BJP and promotes extreme views on India being a Hindu nation.

Modi’s implementation has however been harsher on Muslims than even the RSS appears to like. Mohan Bhagwat, the RSS’s leader, has indicated this and has also implicitly criticised Modi for his egocentric behaviour, using the word ‘ahankara’ (arrogance). That was after Modi combined religion with politics to boost his image as a supreme leader. It was most evident when he cast himself ostentatiously in the virtual role of a Hindu priest at the opening of a major temple at Ayodhya in north India that had been built on the site of a former mosque.

Some observers thought Modi would tone down the Hindutva focus after last year’s general election where he failed to achieve his aims. The relatively poor result drove him into an active coalition with other parties that might have wanted a less controversial approach. Instead, after a pause, the BJP has increased the majoritarian rhetoric, as was evident in the Maharashtra and Jharkhand state assembly election campaigns later in 2024. In Maharashtra there was a rallying cry “if you are divided, you will be killed”, which was seen as a call to militant Hinduism.

Attacks on mosques have continued, and there are confrontational calls for Hindu authorities to reclaim some prominent sites that the places of worship now occupy, following the example of what happened at Ayodhya.

A controversial citizenship law that offers amnesty to illegal immigrants from neighbouring countries, excluding Muslims, has already been enacted. BJP-controlled state governments have also begun introducing the Uniform Civil Code that outlaws Islamic and other personal laws, But there is no movement yet on an even more confrontational National Register of Citizens that could make Muslims and other minorities vulnerable to discrimination and harassment.

Like Donald Trump in the US, Modi’s populist aim has been to “clean the swamp”. The aim is to enforce his supremacy while entrenching the Hindu doctrine and establishing a new elite.

Political dominance has been partly secured institutionally by appointing supportive and malleable top bureaucrats to the Election Commission of India, while sidelining and sometimes harrassing those who do not fall into line. This has been done to a much greater extent than under previous non-BJP governments. It is not clear how much this has seriously affected polling results, though it has ensured favourable timings of elections and flexible administration of regulations. There have been allegations of electoral rolls being rigged, for example in recent Delhi and Maharashtra state assembly elections.

Other institutions have been the target of Modi’s Hindutva drive. Wider control and influence has been established through the appointment of well-disposed candidates to be the Supreme Court of India’s chief justice and to occupy the court’s other (maximum 33) judicial posts. All governments do this, but it is currently being taken to an extreme.

The decline of the Election Commission’s and Supreme Court’s independence can of course be fairly rapidly reversed by a future government making fresh appointments. After Modi’s poor result in last year’s election, the Supreme Court even felt emboldened to take contrary decisions and make independent statements. These included rulings against “bulldozer justice” where state governments demolish homes and properties of people, especially Muslims, accused of alleged crimes.

More insidious and long lasting however is the politicisation of academia through the appointment of pro-Hindu nationalist administrators and academics at all levels of university life, reducing scholastic autonomy and freedom for research. Changes in curricula and rewriting of textbooks have reinterpreted history with Hindu-centric narratives that also influence the arts. There has also been suppression of student protests, sometimes with harsh police action and particularly in leftward-leaning institutions such as Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and also in the city’s Jamia Millia Islamia.

There has been some impact in the armed forces where Modi has linked Hindu nationalism with patriotism, drawing senior officers and others towards the BJP. That leads to higher ranks of the military growing compliant with current Hindutva political thinking, potentially reducing the values of an apolitical, secular and professional army.

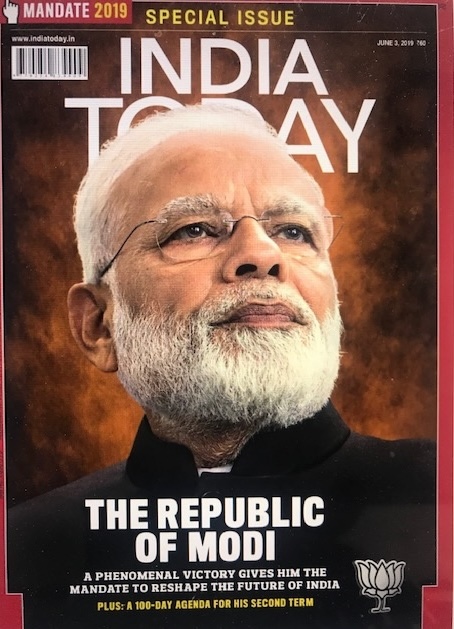

Attacks on dissent and freedom of speech have led to journalists, editors, activists, and academics critical of the government facing violence including killings, arrests, harassment, and legal action with sedition and defamation laws treating dissenting voices as anti-national and unpatriotic. Much of the media is owned by Modi-supporting tycoons, notably Mukesh Ambani, and there is extensive self-censorship. Some papers like the Indian Express and the India Today group do run critical pieces, but that is carefully balanced by other coverage.

It is important to note that none of these institutions is yet in operational crisis, though they have lost independence and considerable public respect. Despite its bias and lower-level allegations of corruption and vote rigging, the Election Commission presided over last year’s general election, which was judged to be reasonably fair, though there were opposition claims to the contrary. The Supreme Court remains the unchallenged pinnacle of the justice system, and universities continue as places and spaces of learning, discussion and debate, and political challenges.

In the final analysis, Modi’s government has succeeded in transforming India’s economy and global stature and boosted development and social services, but it has also sowed and cultivated deep division and undermined democratic freedoms and institutions.

For some, the economic and other positive reforms are enough to consider Modi’s tenure positive. For others, the erosion of democratic norms, the social divisions, and the undermining of religions and other freedoms overwhelmingly overshadows the achievements and puts India’s future as a secular open democracy at risk.

Nevertheless, with India lacking any other viable national leader or governing political party, there is a growing feeling that Modi’s government is better than the inadequate alternatives, especially at a time of international turmoil.

Leave a comment