Dramatic, though phased, reductions in tariffs plus other deals

Diplomatic significance that a Labour Government can work with India

LONDON: For decades India and the UK have eulogised about their common heritage, their shared values and common language, hoping a series of isolated initiatives based on good intentions would yield material results in terms of increased trade and investment partnership. But the dreams of future potential have never been fully realised, even though two-way trade has grown from some £3bn in the early 1990s to £43bn last year.

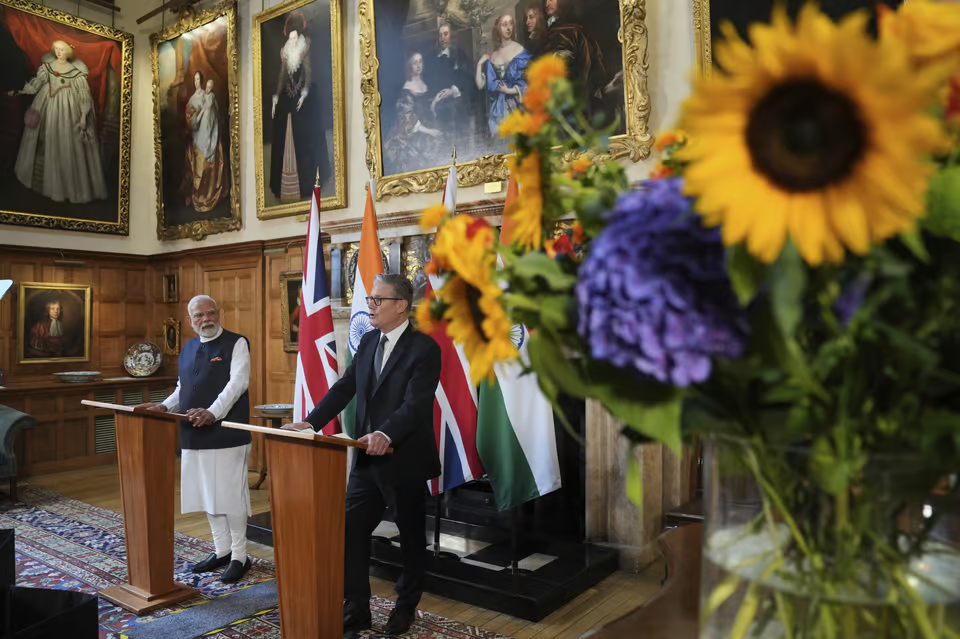

The signing of a multi-billion-dollar free trade agreement during Narendra Modi’s official visit to the UK this week (July 23-24) should gradually change that after the years of unrealised hopes. “Today marks a historic day in our bilateral relations,” Modi said during a signing ceremony at Chequers, the UK prime minister’s country residence. The aim is to double two-way trade to over £80bn ($112bn) by 2030.

After three years of tough negotiations, there are to be wide-ranging phased tariff reductions, though the deal still has to be approved by the UK parliament, which might delay implementation till next year. There is also fresh and expanded co-operation in other areas including visas plus defence, technological cooperation, education, climate and security.

Britain has signed recent trade deals with the US and the European Union, but prime minister Keir Starmer said at Chequers that the Indian deal was the “biggest and most economically significant” the UK has concluded since it left the European Union in 2020.

For India, it is the first major free trade pact outside Asia since it decided not to join the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2019.

The deal is significant diplomatically because it shows that Starmer has persuaded India that his Labour government is not shackled by the Labour Party’s historic pro-Pakistan stance over the disputed region of Kashmir and by over-riding sympathies for protests by minorities in the UK. Starmer has also approached the negotiations with a more determined workmanlike approach than Boris Johnson and other Conservative leaders.

Viewed from India, the deal is significant because it shows how Delhi is widening its bets now that its developing alignment with the US has been upset by President Donald Trump’s erratic style of government. Put more formally, the deal is in line with India’s foreign policy of multi-alignment.

Modi’s 24-hour visit

Modi was said to be on a two-day visit, but he was only in the UK for 24 hours and did not come to London. He stayed the night he arrived in a hotel near Luton where he was feted by members of the Indian community. He flew in and left from the capital’s third airport at Stansted in Norfolk, near the Sandringham country home of King Charles where he met the King at the end of the visit.

In between he was at Chequers, Keir Starmer’s country retreat not far from his hotel, where he also met businessmen and the Indian diaspora. This unusual avoidance of London meant there was no risk of the sort of mass demonstrations that greeted Modi on his first visit as prime Minister in 2015, when Parliament Square and surrounding streets were closed and barricaded.

Modi was far from popular at the time, mostly because of mass deaths in 2001 in Gujarat when he was chief minister. The Times ran a headline saying, “Hold your nose and shake Modi by the hand”, while The Guardian went over the top with “India is being ruled by the Hindu Taliban”.

But times have changed, and the world has moved on. Since he became prime minister in 2014, Modi has rebuilt India’s image internationally as the world’s fourth largest economy. He has also built his own image as an international, though still controversial, statesman. While his critics now focus on his government’s authoritarian and Muslim-restricting Hindu nationalism, the world’s focus is on how to boost and manage trade in an environment dominated by Trump’s unpredictable tariffs.

The Economist even said this week that the deal was “a rare win in the Wild West of global trade”, adding that “the global uncertainties of Mr Trump’s tariff vendettas make the pact stand out as an unusually well-negotiated and orderly way of boosting global trade.”

Moves towards an agreement began in 2021 but negotiations, which started a year later, failed to meet Boris Johnson’s glib target of India’s Diwali festival in November 2021. They were then delayed last year by general elections in both countries.

First announced in May, the agreement means that tariffs on more than 90% of UK exports to India will be cut over a decade with the largest reductions on cosmetics, clothes and food and drink. Duties on scotch whisky, which make up the bulk of the UK’s current exports, will fall from 150% to 75% immediately and eventually to 40%. In return, 99% of Indian exports to the UK, ranging from gems, textiles, leather and garments to engineering goods, and processed foods, will face zero tariffs.

Tariffs of up to more than 100% on British cars will slide to 10% by 2031, but will be restricted by a quota system till 2046. Negotiations are said to have been extremely tough, with India protecting its motor manufacturing industry. The FT has reported that British car makers are “underwhelmed” but added that government officials said the deal provided “unprecedented liberal access to India’s rapidly growing middle class”.

The deal has not given the UK the access it wants into India’s financial and legal services. Talks are also continuing on a bilateral investment treaty aimed at protecting British and Indian investments in each other’s countries, and on UK plans for a tax on high-carbon industries that India believes could hit its imports unfairly.

This was Modi’s fourth prime ministerial visit to the UK. Following the first one in November 2015, he came in 2018 for a Commonwealth Heads of Government biennial conference, where he played a positive role by helping the Queen ensure that she was succeeded as head of the organisation by Prince, now King, Charles. In 2021, he visited Glasgow for the Cop 26 climate change conference where his policies appeared positive, but India then broke ranks and helped China to water down a resolution phasing out coal-generated electric power.

Modi has been in the UK at a time when India and China are improving their fractured relations, marked with an announcement a few days ago that Chinese tourists could apply f for Indian visas for the first time in five years.

Relations are also improving with archipelago island state of Maldives where Modi stopped for a day on his flight back to Delhi. The current Maldives pro-China government, which was elected 18 months ago on an “India-out” platform, hosted Modi as guest of honour at its 60th independence celebrations yesterday. If this proves to be a real change, it will be a significant gain in India’s attempts to resist China’s development of close relations with all its neighbours.

India’s next target is a trade deal with Trump, who this weekend is at his two golf courses in Scotland where he will meeting Starmer. The US president first announced 26% tariffs on Indian goods on April 2, but postponed that till a new deadline of August 1. India’s trade minister, Piyush Goyal, said in London a couple of days ago that negotiations were making “fantastic progress”. There are however reports that India is testing how the markets would react if a deal is not done by the deadline.

That level of uncertainty no longer exists on the India-UK deal, which will soon challenge both countries to shake off past under-performance and deliver in terms of multi-billion trade and investment.

Leave a comment