Kew invited the artists, the Singh Twins, to explore Kew’s archives and plants, and track the links to colonisation

The important role played by Britain’s Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in the country’s controversial colonial history is being graphically exposed and criticised by an art exhibition that challenges the image of the peaceful green spaces with their rare plants, magnificent trees and iconic glasshouses.

Kew Gardens, as it’s usually known, invited the Singh Twins (below), who are established artists of Indian origin living in Liverpool, to focus their critical approach to the British empire on the institution’s massive and rare botanical collection contained both in extensive archives and as live plants.

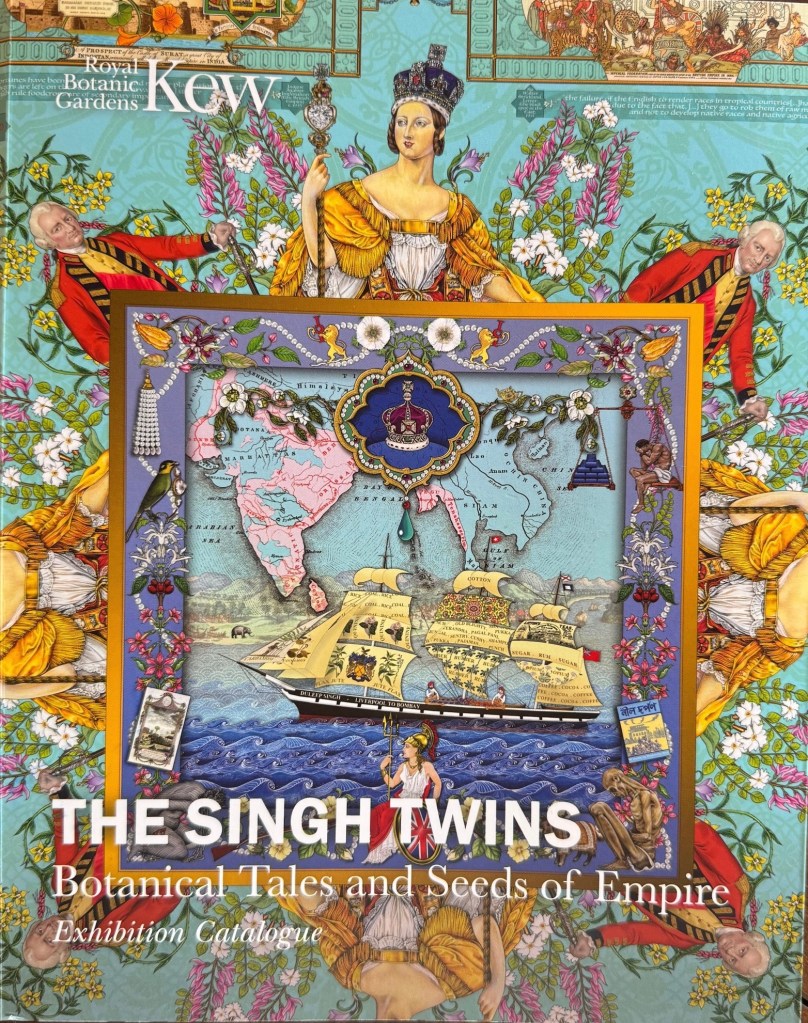

The result is an exhibition titled SINGH TWINS: Botanical Tales and Seeds of Empire that is open till April 12 in the Gardens’ Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art. It reflects the way that museums and other British institutions have become increasingly willing in recent years to look into their collections and expose what the twins call “the darker side of what is revealed”.

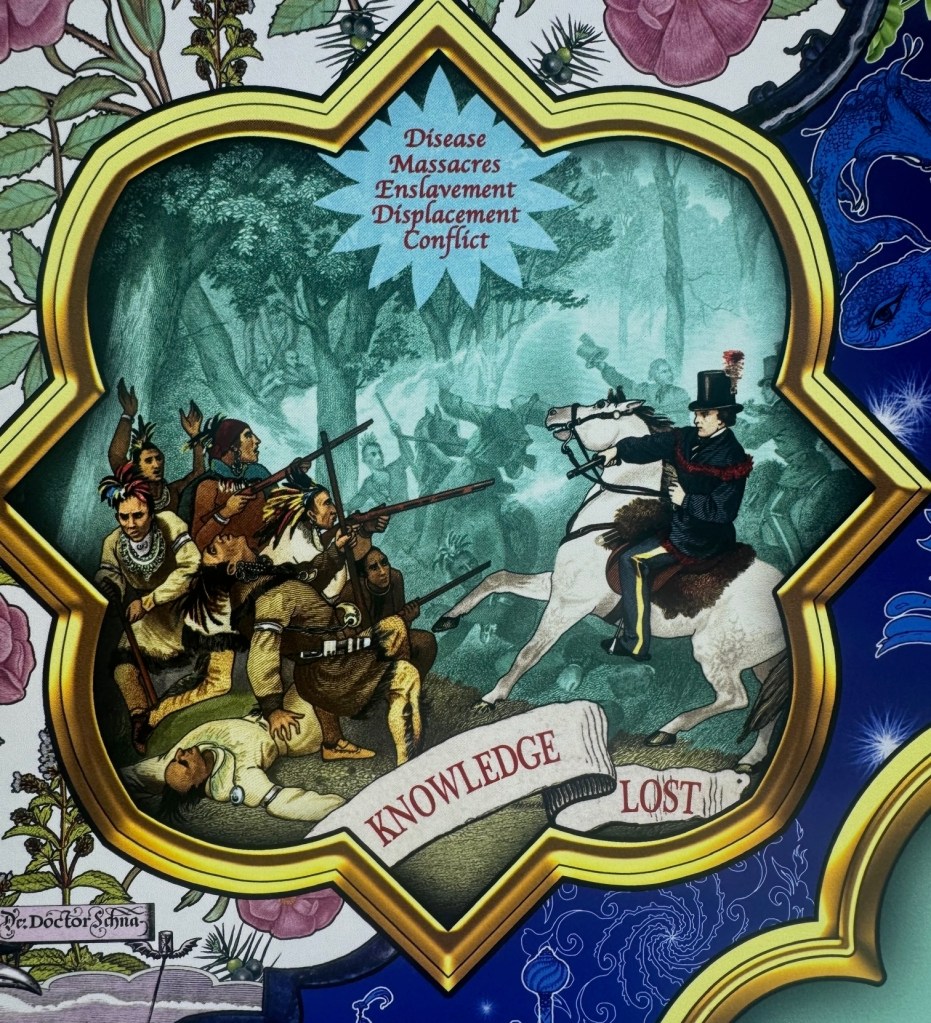

Kew’s role in colonisation comes alive with a dramatic series of large back-lit works of art on fabric. These show how plants such as cotton, spices and dyes played a pivotal role in Britain’s colonial expansion as well as more positively in the transfer of botanical knowledge and experience across continents. There are also smaller works on the symbolism and significance of plants in global trade, and a tough film highlighting the negative message.

“The Singh Twins were a natural choice because of their unique ability to combine rigorous historical research with a powerful contemporary artistic voice,” Maria Devaney the galleries and exhibition leader told me.

“Kew’s history is closely entwined with Britain’s imperial past, and it’s important to acknowledge and respond to those complexities. We have a responsibility to engage honestly with our own history and with the wider histories that shape our collections and our work today. This is part of Kew’s ongoing commitment to inclusion and to presenting, plants, science and culture in their full historical contexts”.

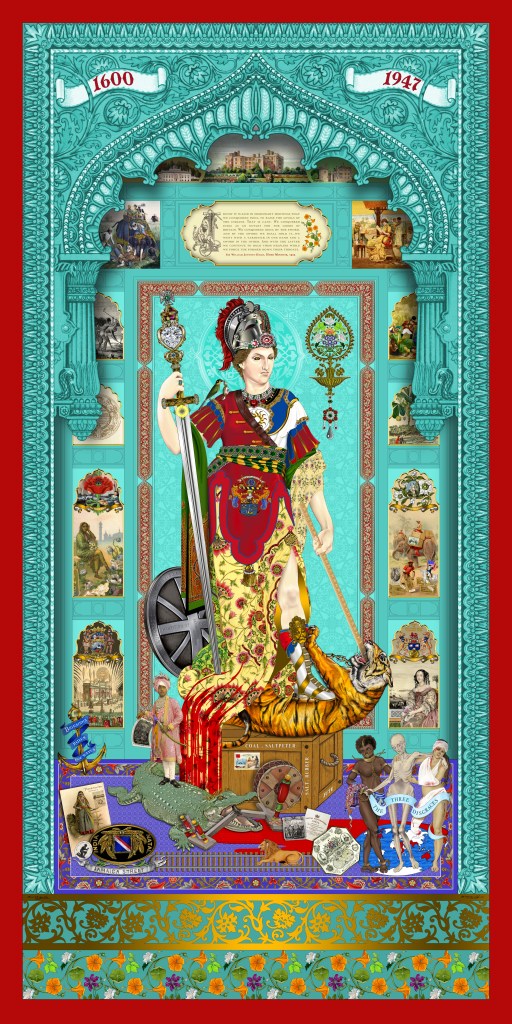

The toughest message comes in an allegorical work titled Imperialism: By the Yardstick and Sword that focuses, says the exhibition’s coffee-table style catalogue, on “the impoverishment and enslavement of India under western colonial expansion and in particular British rule”.

The main figure is a female warrior representing Western Imperialism standing above a tiger, piercing it in the mouth. Smaller images surrounding the figure illustrate the exploitation with a quotation saying, “India was ruthlessly conquered as an outlet for British goods”, which actively contributed to the “destruction of India’s industries”.

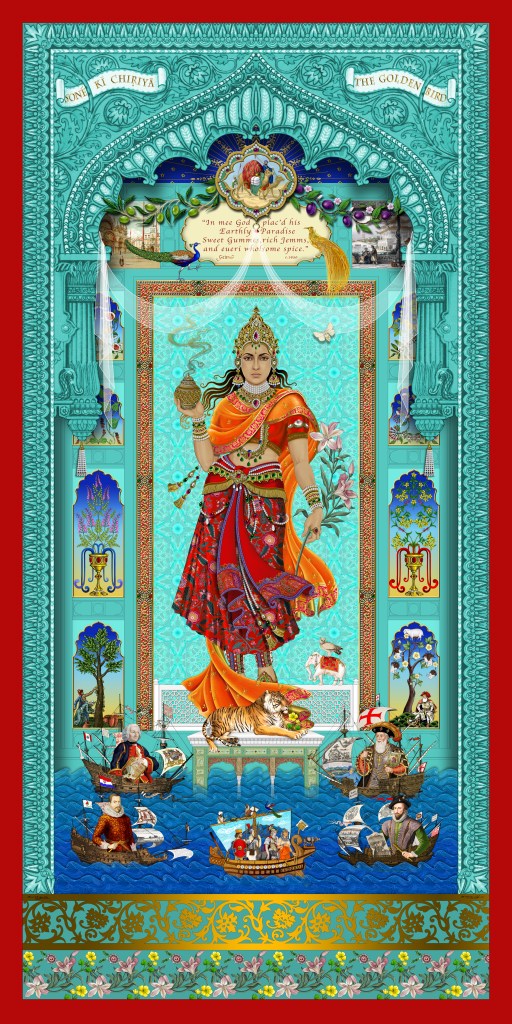

The Golden Bird: Envy of the West “shows an allegorical figure representing pre-colonial India” before the British arrived. It was a “fabled land of untold riches and prosperity”.

Dying for a Cuppa deals with the “British colonial history of tea”, highlighting the tea trade’s “links with sugar and opium, commodities inextricably linked to enslavement, conflict, violence, land grabbing, deforestation and drug addiction”.

The Twins say Kew was aware of their work and had seen an earlier exhibition in 2018 on the same theme in Liverpool. This demonstrated, they say, Kew’s “willingness to look at its collections in a different light and bring out those histories….they knew exactly what they were buying into”. When the Twins pointed out that they would be looking at the “darker side” of Imperialism, they were told “this is actually what we want you to do”.

They were “overwhelmed” by the breadth of Kew’s documentation, processing, and archiving of material relating to plants, but they had already done research and “knew what we wanted to get out of it”. That was to look at colonial links in botany following on from their Liverpool exhibition in 2018 where they focussed on similar narratives connected to India’s historical trade in cotton and other textile links.

“Kew was a central cog in the economic exploitation of plants, playing a key role in the Empire’s collection transportation and cultivation of commercial crops such as cotton, rubber and cinchona,” says Richard Deverell, the Gardens’ director and ceo, in an introduction to the catalogue.

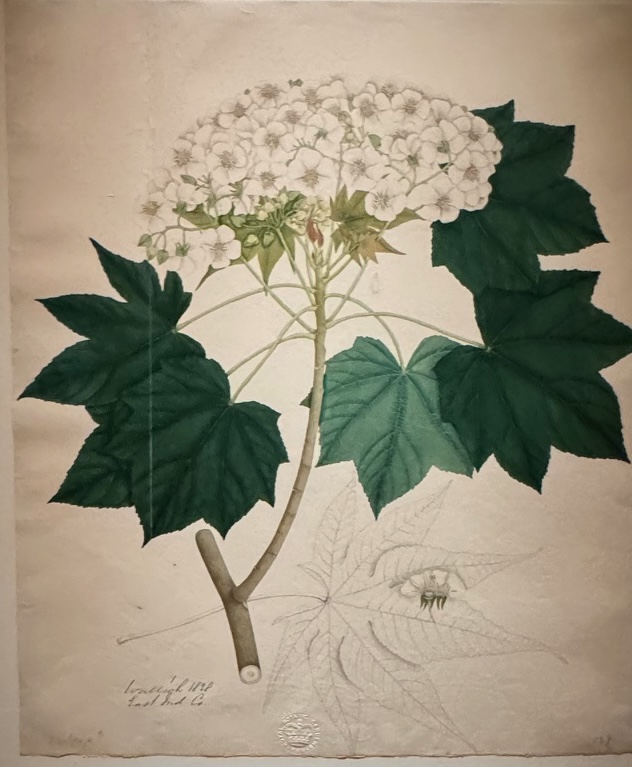

Showing alongside the Twins’ works, under an overall Flora Indica title, is the first-ever public display of 52 rediscovered botanical watercolours (above) by Indian artists who were commissioned by British botanists between 1790 and 1850. Hidden for over a century, the works show how artists helped shape botanical knowledge from India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar. The Twins studied these and other archived works commissioned by Britain’s East India Company that controlled India for a century till 1858.

Over the past 17 years, the Twins have been exploring and exposing what they describe as the “exploitative nature of colonialism and empire”. They are proud of having “always spoken loudly about things we believe”.

Born in the UK with a Sikh father who emigrated from India in 1947, Amrit Kaur Singh and Rabindra Kaur Singh are identical twins in their late 50s. They always dress alike and talk together, interrupting and finishing each other’s sentences. Their father, and their Sikh background, flow through many of the works.

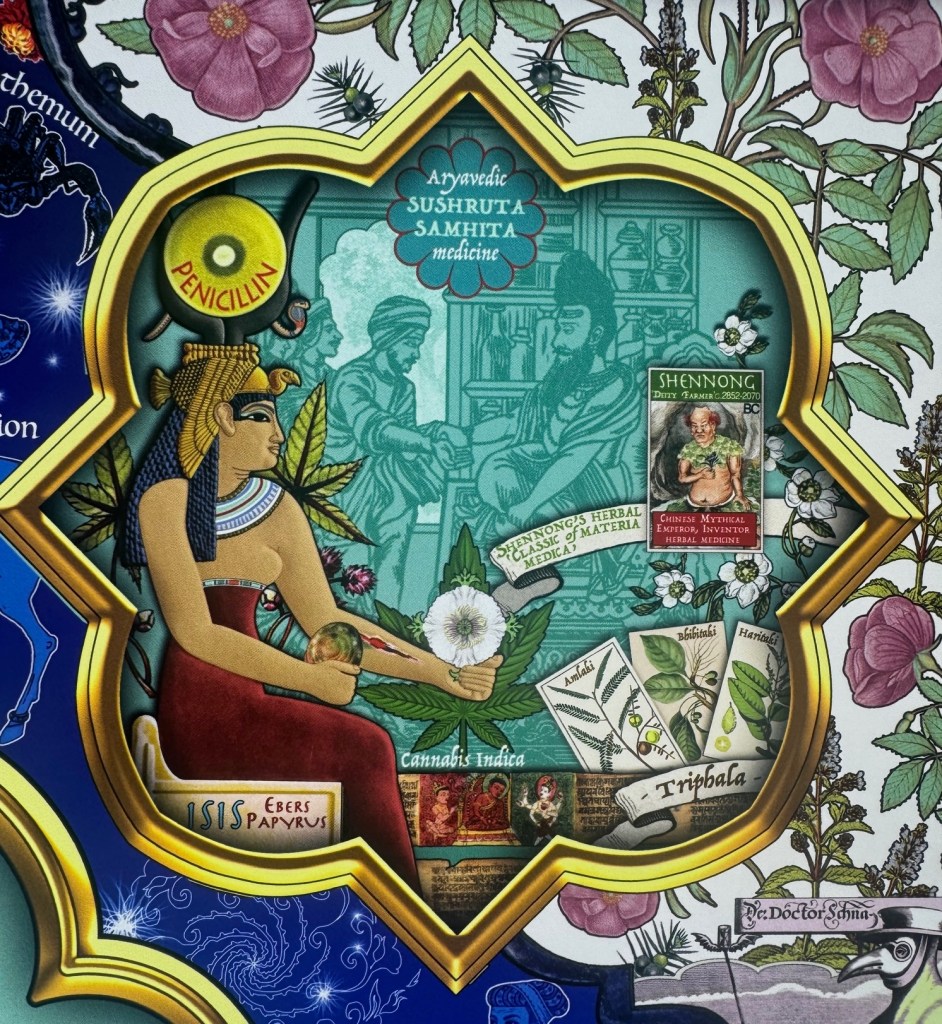

The Twins adapt the intricate and colourful style of Mughal miniature paintings into a form of pop art where a series of individual small compositions cluster around a central image, together telling a multi-illustrated story. With up to around 15 images in a single work, the Twins estimate that the Kew exhibition has more than 200 compositions.

That was apparent when I first interviewed them, in 2011, at an exhibition in New Delhi that combined challenging the misuse of power by the Indian and other governments with recording the lives of Indians living in Liverpool and elsewhere in the UK. “They have been fighting convention since they were at university in Liverpool,” I wrote. The show included Partners in Crime, Deception and Lies with US president George W. Bush and UK prime minister Tony Blair standing on a burning blood-strewn globe of the world after the invasion of Iraq.

That was the year that they were both awarded an MBE, becoming Members of the Order of the British Empire. Their art had been shown in 2010 at London’s National Portrait Gallery, which describes their work as continuing “a long tradition of artistic interaction and influence between cultures”.

As students in Liverpool, they were told that the Indian miniatures style was no longer relevant and that they should be learning from Matisse, Gaugin and Picasso. “We said that Gaugin and others had been influenced by India and other foreign works, and that we were being denied our own way of expressing ourselves,” was their reply. “There was pressure to conform to Western ideas, but we were challenging accepted notions of heritage and identity”.

Their interest in the negative aspects of colonialism began when they were part of a British Arts Council trip in 2014 to the French city of Nantes in Upper Brittany. There they visited the Château des Ducs museum that has a large section on slavery marking the Atlantic coastal port’s significant role in the international trade, similar to Liverpoool’s.

They also found displays of Indian textiles commissioned by French traders to be sold to African tribal chiefs as part of the slave trade, which made them realise the wide range of the trade beyond the transatlantic triangle

That led to the 2018 exhibition, titled Slaves of Fashion, at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery where the Twins developed their criticism of empire by focussing on the history of Indian textiles, especially cotton, enslavement and luxury consumerism. That is “a global story of conflict, conquest, slavery, environmental exploitation, cultural exchange and changing fashion,” they say, relating it also to current debates on ethical consumerism, racism and the politics of trade.

The Kew exhibition’s hard-hitting short film King Cotton: An Artist’s Tale was first shown in Liverpool and focusses on textiles. Set to a poem written by the twins and narrated by Amrit, it pulls no punches with lines like: “Torture was used to enforce taxation, and monopoly of salt caused devastation – to the mases steeped in poverty…..so that England’s exports might expand, thumbs were broken on weavers’ hands… …the tools of their trade were seized and smashed while Indian servants were routinely thrashed”.

The film’s rhyming poetry is good but there will be objections to some of the criticisms, notably weavers’ “thumbs being broken” that was first voiced in 1853 by Karl Marx. An earlier report in 1772 by William Bolts, a Dutch-born British merchant and employee of the East India Company, suggested that winders of raw silk were treated so badly that they cut off their thumbs to avoid being forced to work, though that is also represented in the film.

Critics will say that the show does not illustrate sufficiently the world-wide benefits reaped by early explorers and botanists who faced extreme challenges travelling to Asia and elsewhere centuries ago.

The exhibition includes a work, Cinchona: What’s in a Name marking how in 1860 a British expedition to South America smuggled out cinchona seeds and plants that led to the development of quinine to treat malaria. Planted extensively in British India and Sri Lanka those stolen seeds and plants saved millions of lives, until an artificial synthesis of quinine was developed in 1944, but the Twins introduce it negatively saying it was “significant in the colonisation of tropical countries”.

“Plants are an essential resource for human survival and they are also the foundation of practically all life on earth,” says one prominent habitat conservationist. “Yes, exotic plants were collected clandestinely in colonial times, just as they are today. But the efforts of those early collectors also brought huge benefits, particularly in the field of medicine”.

That does not however reduce from the importance of the Twins work, displaying in masses of intricate and highly colourful works, the links between botany and the negative side of empire

lovely! both the art and the article

By: dillikidiva on January 10, 2026

at 5:21 pm

Very interesting.

Regards.

By: suvidha10 on January 10, 2026

at 4:18 pm