Sir Mark Tully was also once named the “Battered Sahib”

Remembered for the aptly named “Something Understood” radio programme

Perhaps no-one in living memory has spanned the two cultures of Britain and India as sensitively and closely as Sir Mark Tully, the BBC’s veteran broadcaster, who died in New Delhi age 90 today (January 25), a Sunday as he would have wished.

His loss will be felt throughout South Asia and across the world where listeners to the BBC will remember the rich tones of his warm but powerful voice, not just reporting on India and its neighbours, but also leading Something Understood, a weekly faith and music-oriented BBC radio programme.

I first met Mark in Sri Lanka during the Tamil uprising of 1983 and quickly realised he was a tough and persistent reporter, but with a ready smile for people he met, charming them with fluent Hindi as well as his cultured English. He was a kind, caring and religious man, who once thought of becoming a priest. His broadcasting, and later his books, were often strongly influenced by a deep sense of right and wrong, which partly led to strong negative views about modern development.

Mark Tully immersed himself in the countries he covered and developed a wide circle of friends and trusted contacts ranging from poor villagers to those at the top of government who frequented his home in Delhi. They all helped him deliver revealing reports that uncovered the stories of a region going through massive change. Later his books, with iconic titles like No Full Stops in India that was published in 1991, vividly portrayed aspects of life in the remotest parts of the subcontinent.

Famous on the BBC’s radio air waves across South Asia, he was scrupulous about his detachment, even though he was specially lauded in Pakistan in the 1980s. People there listened out for his radio reports on the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) that aimed at unseating the country’s military dictator, General Zia ul-Haq. I remember how, in a country where the media had little freedom, the BBC brought hope crackling down the airwaves with news of the MRD’s rallies and protests.

The Bangladesh media has remembered how he performed a similar service during the 1971 war that led to the country being created out of what was Pakistan. “His BBC radio reports became the people’s chief source of authentic information,” says The Daily Star. He was named a Foreign Friend of Bangladesh in 2012.

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, described Mark Tully on X as “a towering voice of journalism”. His “reporting and insights” had left ” an enduring mark on public discourse”.

Mark was the BBC’s New Delhi-based bureau chief for 20 years and foreign correspondents were frequently chased by children calling out “Are you Mark Tully, Are you Mark Tully?”. One day, near the Pakistani city of Hyderabad, a colleague and I were asked the question at a chai stall. “Yes, I am!”, I said, exasperated by the repeated questions. Stirring the chai, the stall holder spoke to me in his own language and, when I didn’t reply, declared “You’re not Mark Tully, you don’t speak Urdu!”.

Sometimes the Tully name was used more threateningly. In December 1992, he had become the symbol of all that was resented about the international media by the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Hindu extremists who were targeting foreign journalists after demolishing a revered sixteenth century Muslim mosque in Ayodhya. (A new Hindu temple was opened on the site by prime minister Narendra Modi early in 2024).

Tully escaped with some other journalists, rescued by a nearby temple priest. “We were surrounded by a huge mob screaming, ‘Death to Mark Tully!’ and ‘Death to BBC!’,” he later told the Los Angeles Times for a profile headed “The BBC’s Battered Sahib: Mark Tully has been expelled by India, chased by mobs and picketed. He loves his job”.

His big events ranged from India-Pakistan wars, the Russian occupation of Afghanistan and the foundation of Bangladesh, to the uprisings in Sri Lanka and elsewhere. I saw him centre stage on stories like the Indian army’s storming of the Sikh Golden Temple in Amritsar, the assassination of prime minister Indira Gandhi, and Union Carbide’s Bhopal gas disaster. He was always aware that what he said on the air waves could have a much more immediate and maybe cataclysmic impact than most newspaper reports.

He irritated and infuriated successive governments and was expelled from India along with other foreign correspondents during Indira Gandhi’s 1975-77 State of Emergency, but was awarded the highest civilian honours. In India he received the Padma Shri (for distinguished service) in 1992 and the Padma Bhushan (for distinguished service of higher order) in 2005. In the UK, he was knighted for his contribution to journalism in 2002, though he rarely used his full Sir Mark Tully title.

Mark was born on October 24, 1935, in Calcutta (now Kolkata), where his father was with Gillander Arbuthnot, a British managing agency firm. His mother’s family had worked for generations in what is now Bangladesh.

He was brought up, colonial style, with a European nanny, then at a British boarding school in Darjeeling north of Calcutta. His teenage school years were spent at Marlborough College in the UK.

That was followed by Trinity Hall at Cambridge University, where he studied theology, but abandoned the idea of becoming a Church of England priest after two terms at a theological college.

Mark often said that he didn’t think his lifestyle would have fitted with being a priest, mentioning beer and whisky, and sometimes talking about his complex personal life. “There’s always been a dichotomy in my character – very religious, yet morally really rather bad,” he told The Independent newspaper in 1994. “I simply wasn’t confident of my own moral integrity,” he said in a interview with The Hindu newspaper. “And the Church mattered enough to me — as it still does — so that I didn’t want to let it down.”

He remained married to his wife Margaret after she returned to London from India in the early 1980s, and spent the rest of his life based in Delhi with his partner, devoted assistant, and sometimes co-author Gillian (Gilly) Wright

“It reflects great credit on my wife and on Gillian,” he said in the Independent interview. “After such a long relationship, I didn’t want a divorce and have to write ‘finis’. I wanted to remain friendly with her (Margaret) and my children.” Asked about this in a 2004 interview with the Cambridge University alumni magazine Cam, he replied: “I can’t speak for my wife or Gilly….Of course, I am not comfortable with the situation, not least because it doesn’t conform with the teachings of the Church”.

After abandoning what he saw as his vocation as a priest, he did not know what to do, so taught for a while and then spent four years working with a housing charity in Cheshire.

His life was transformed when he joined the BBC in 1964. A year later he moved to India, initially in management but quickly transferring to reporting, becoming the bureau chief, a post he held for 22 years. Aided by his deputy, Satish Jacob, and in later years by Gilly, he travelled extensively across the sub-continent, building relationships that included top political leaders and covering ordinary people’s miseries and their gradually changing lives as well as the big events.

If there has been criticism of his coverage, it is that he was – and remained – too critical and opposed to the development and modernisation that has replaced traditional lifestyles and attitudes. He did not of course advocate continuing poverty or a lack of development, but he refused to accept that western-style consumerism and other forms of change were the way to achieve progress. He was also a virulent critic of the current Indian government’s Hindu nationalism.

No Full Stops had been “didactic”, he later admitted (in the preface to his next book) pleading that, along with economic growth, it was also necessary to “protect the country’s ancient culture, not merely ape….the sterile materialism of the modern Western culture”.

He was not afraid to air unfashionable views, as he showed over India’s widely condemned caste system on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 2003. “We have to look to the good and the bad in the caste system,” he argued. “The good side of it is that it offers security, it offers companionship, a community to belong to and that sort of thing.”

Mark has said that his passion for India was greater than his passion for journalism. He was happiest travelling the country talking to contacts and reporting and commenting on radio what he saw and heard.

He did not easily adapt to television and the BBC’s increased commercialisation, and thought change should come by “evolution not revolution”. That led to him resigning from the BBC in 1994 after he was told to stop voicing his criticisms. But he continued to do occasional programmes – in 2017 for India’s 70th year of independence, he and Gilly made a memorable cross-country journey that combined his hobby as a railway buff with reflections on the emerging India,

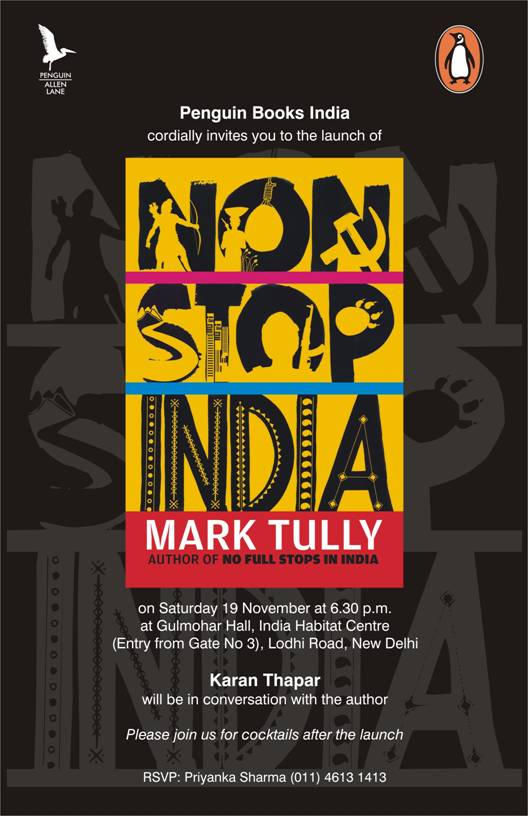

Away from the constraints of daily reporting, Mark became a prolific author producing a total of more than a dozen books that vividly explored life in India with titles like India in Slow Motion and India’s Unending Journey as well as No Full Stops. Recently he was in the final stages of editing a memoir-style autobiography that Gilly will now complete.

Mark was also celebrated as the leading host on Something Understood, the BBC Radio 4’s Sunday morning programme of words and music that started in 1995. Listeners tuned in from all over the world. Focussed around faith, spirituality, and human life, this took him back to his original vocation till the BBC ended the series in 2019.

Regretting the BBC’s decision, Mark told the Radio Times magazine that he felt sad because he knew a lot of listeners liked it. “They say two things to me about it – that there is nothing else like it on the radio, and that this is what radio should be all about. And I think that’s true.” So many listeners instantly mention this when they hear the name Mark Tully – and tune in when the BBC runs repeats.

Mark is survived by his wife Margaret and four children, Sarah, Sam, Emma and Patrick, and by his partner Gillian.

I first met Mark in 1975 when we were colleagues in the BBC radio newsroom in Broadcasting House (BH). He had been withdrawn when Mrs Gandhi’s emergency required him to sign a censorship agreement.

Over the past 50 years I have enjoyed his friendship and that of his wife Maggie and their children, and of his partner Gilly. With my wife Roopa Sukthankar and our son Alex, we holidayed with Mark and Gilly all over India, though to my regret never made it to his birthplace Calcutta.

Many stories have been told of him, but not this one. Towards the end of a newsroom night shift the radio programme “Good Morning Scotland” called me on the foreign news desk to ask if they could two-way him about his book “No Full Stops in India”. After the interview was done, he called to say it had gone well, but added “I almost cracked several times, but I couldn’t because it was live. They kept referring to the book as “No Fool Stops in India”. Over and over again. You know, the way the Scots pronounce the word “Full”. All the time I was trying not to giggle.”

Graham Webb, Bombay, 3 February 2026

By: zorrorad691ff192db on February 3, 2026

at 3:39 pm

I first met Mark Tully in Delhi, at 1 Rattendon Road—now known as Amrita Shergill Road—at Jognath Chatterjee’s home. In those days, the house was a gathering place for remarkable minds. The adults would sit together—people like Krishna Reboud, Mark Tully, Tyeb Mehta, and my father, Subho Tagore—talking late into the evening.

We children lived in a different world entirely. We played with our friends—Joya Chatterjee, who would later become a famous historian, and Ini, who would go on to be a post-modern architect—running in and out of the back garden and Lodhi Garden, which adjoined the house. It was a simple time, yet layered and complex in ways I only understand now. The evenings were beautiful, filled with warmth, conversation, and the quiet sense that something meaningful was always unfolding.

Sometimes, curious and drawn in, I would wander up to the main living room where the adults gathered. I didn’t always understand what was being said, but I listened closely. I remember watching Mark Tully with wonder and awe—his voice, his presence, the way others leaned in when he spoke.

Life carried me to the US, and Mark Tully reappeared in a different context—through South Asian news stories on the BBC and other media outlets. The personal memory merged with the public figure. He was a comforting presence. I alway trusted his views and comments about the Subcontinent.

Today, it feels like a sad day for journalism. But Mark Tully leaves behind more than loss—he leaves a standard. One rooted in depth, integrity, and genuine engagement with the world. A legend has passed, but his legacy endures. Rest in peace.

By: Sundaram Tagore on February 1, 2026

at 2:54 am

Sad to hear of his passing, glad to have known the great man, whom I first met when he arrived to run BBC coverage of the anti-Tamil pogrom in Colombo in July 1983, and closely interrogated the few international reporters (I was filing to the Guardian and the Observer) already on the ground, among many other people in his contact book. One of our late evenings under curfew at the Galle Face Hotel is a longer tale. Soon after in Pakistan’s Sind Province during some rather bad trouble that August, people approached Western journalists asking, “Are you Mark Tully”. It was a joke to point to the corr next to you and say, “No, he is”… and wait to see if we would be garlanded or abused! That was when almost no one knew what face was attached to the voice on the radio that they so admired for offering fact-based news… and sometimes reviled for that same reason!

By: TR Lansner on January 27, 2026

at 10:06 pm

He served in Royal Dragoons

By: Roddy Sale on January 26, 2026

at 3:31 pm

He served in the Royal Dragoons .

By: Roddy Sale on January 26, 2026

at 3:30 pm

A wonderful tribute to a great reporter and even greater human being, capturing in a few words the range of Mark’s life and achievements. To have Mark as a friend was a privilege. Gilly’s effort to complete his autobiography will be a gift to Mark’s following around the world. Mark was an original ‘influencer’, driven by values and professionalism, not by a market.

Ashoke Chatterjee ashchat@prabhatedu.org

By: Ashoke Chatterjee on January 25, 2026

at 11:58 pm

Very nice piece. I recall being hosted by Mark and Margaret whi

By: dazzling4212fcb630 on January 25, 2026

at 10:04 pm