Anne Wright, probably the last of British expats who stayed after 1947

Born into an old colonial family she led the way on conservation

The recent death in central India of Anne Wright, age 94, marks the end of an era. This wildlife campaigner, tiger enthusiast, horse breeder, party lover, and friend of leading politicians and royalty, was one of the last – and maybe the last – of the British expatriates who stayed on after independence in 1947.

Anne Wright died on October 4 after a long illness at her family’s Kipling Camp jungle resort on the edge of Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh. She was cremated, as she would have wished, in the jungle later that day under the stars.

In 1929, she was taken when she was just a few months old to the wilds of central India where her father, Austen Havelock Layard, who was in the Indian Civil Service, was posted. She spent the rest of her life in the country, apart from schooling in the UK, and took Indian nationality in 1991.

One of her early memories was standing, when she was five, with her younger sister and governess on the Kings Way (later Rajpath and now Kartavya Path) in New Delhi. Wearing large white topis (sun hats), they were watching her father, by then the city’s Deputy Commissioner, process past with the Viceroy Lord Willingdon in 1934.

At Mahatma Gandhi’s cremation in Delhi in January 1948, she sat with members of the family of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last British governor general. She remembered being terrified by the vast sea of people. While visiting her friend Rita Pandit, prime minister Jawaharal Nehru’s niece at his Teen Murti residence in Delhi, they went into his bedroom where she saw a photo of Edwina, Mountbatten’s wife, on the bedside table – poignant evidence of the Edwina-Nehru relationship.

It was a grand life. She told John Zubrzycki for a book he was writing on the Jaipur dynasty, how as a young bride in the 1950s she had gone as a guest of the royal family to the princely state of Cooch Behar in what is now West Bengal. At the age of ninety she could “still vividly recall landing on the state’s grass airstrip in the dilapidated DC3 being operated by Jamair”. On arrival, “guests would be met by elephants that would transport them and their luggage to the palace.”

A small, slight and elegant lady with a winning smile and sparkling eyes, she could be tough and determined. She showed this in an extraordinary exchange of letters asking Indira Gandhi, India’s prime minister, to lobby Pakistan’s and Afghanistan’s leaders at a Commonwealth summit meeting in 1983 about the plight of the Siberia cranes.

Gandhi was sceptical about the prospects, but later told Wright both countries had agreed to take protective measures.

Jairam Ramesh, an Indian policy adviser-turned-politician, says he “spent hours” with Anne researching his book, “Indira Gandhi: A Life in Nature”. He writes that “an ecstatic Anne Wright” replied to the prime minister, and raised yet another subject – tapping a major river, the Teesta in north east India to save the Neora Valley. Gandhi later congratulated her on the work of World Wildlife Fund – India, of which Wright was a founder trusteein 1969.

Dasho Benji Dorji, cousin and advisor to the former king of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, remembers how she encouraged him in the 1980s to save the habitat of rare black-necked cranes in the remote Bhutanese valley of Phobjikha that was threatened by plans to grow seed potatoes commercially. In Calcutta, says Dorji, he saw how “traders in wild-life parts were terrified of her – she used to take the police and get them all arrested”.

Anne Layard was born in Hampshire on June 10, 1929 into a privileged British colonial family who had served in India and Ceylon for two centuries. They also included Sir Henry Layard who discovered Nineveh in what is now Iraq. Her father retired as Chief Secretary of the Central Provinces in 1947 and took on an advisory role as counsellor in the new UK High Commission in Delhi. That led her to a friendship with Pamela, Mountbatten’s daughter, one of many such illustrious connections – Mountbatten was in his final year in India.

Her early married life was spent in the social whirl of Calcutta, with her husband Bob who died in 2005. From their home in Calcutta’s prosperous area of Ballygunge, they became the centre of the energetic social life that the already dwindling British expatriate crowd continued through the 1950s and 1960s, India’s political capital had moved to Delhi but Calcutta, now Kolkata, remained a boisterous business hub with a social life that drew royalty from neighbouring Bhutan and Nepal as well as maharajas and other dignitaries.

Bob held senior posts in business and was involved in numerus charities, but is best remembered for managing from 1972 to 1996 the city’s famous Tollygunge Club and acting as the UK’s unofficial but influential consul in West Bengal.

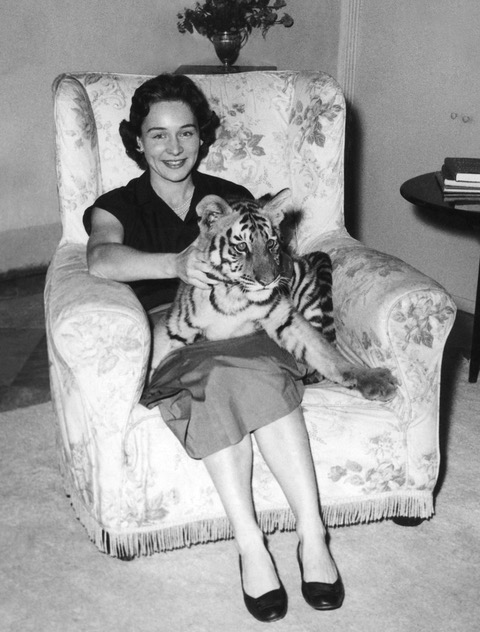

He and Anne were part of the hunting, shooting and polo crowd and raised an orphaned tiger cub and leopard in their home, but this was the generation that put their guns down and campaigned to save them. Their daughter Belinda is known internationally as one of India’s leading tiger conservationists, founding the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI), which she runs. All three have the rare if not unique family distinction of being honoured for their work – Bob Wright and Belinda with OBEs and Anne with an MBE.

In 1970, Anne Wright wrote an explosive article that exposed the illegal trade of tiger skins in a Calcutta market. One of the first detailed documentations of the large-scale slaughter of wild tigers and leopards in India,t was published locally and republished by theNew York Times with the headline “Doom awaits tigers and leopards unless India acts swiftly”, triggering a series of reforms.

In 1972, Anne Wright was appointed a member of India’s elite Tiger Task Force, which produced a remarkable document titled “Project Tiger; a planning proposal for the preservation of tiger in India.” Launched the following year, initially with nine tiger reserves, this was the beginning of one of the most ambitious-ever wildlife conservation projects. She also worked on the drafting of the Wild Life (Protection) Act of 1972, and personally pushed through the creation of a number of protected areas. At the forefront of India’s conservation movement for decades, Wright served on the Indian Board for Wildlife and seven state boards for 19 years.

As a conservationist wrote on Twitter (now X) last week, “”We often speak of how hard it is to be a woman and be a wildlife conservationist in India. If it’s hard now, it was harder before us. Anne Wright tackled it all with courage and determination. And not the simple things — the tough ones of tackling poaching, building laws, and taking on illegal trade”. Wright received the Sanctuary Asia Lifetime Service Award in 2013.

If wildlife was her first priority, her other interest was horses. She played polo, competed in equestrian events and took up breeding thoroughbreds at her stud farm on the outskirts of Delhi. She kept her best for the Winter season of 2000-2001, where her mare, Fame Star, waltzed away with the Calcutta Gold Cup and The Indian Champion Cup.

Jon Ryan, a friend who took her to the secure stabling area at Royal Ascot to see the best thoroughbreds and talk to the stable staff, says “she seemed to find that far more exciting than the grandeur and the pomp of the royal meeting”.

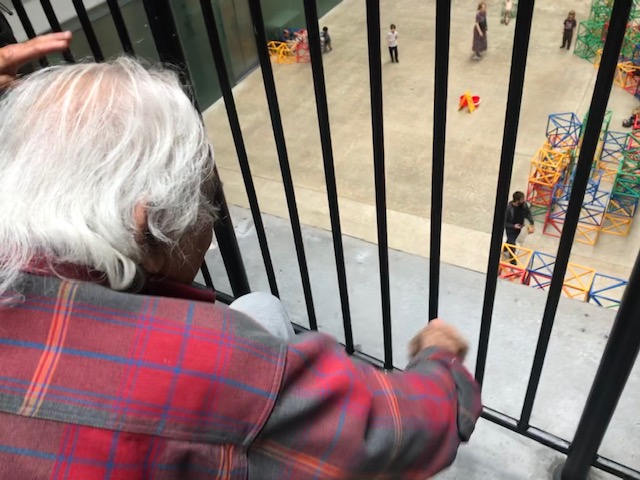

Kipling Camp was the first private wildlife resort in central India when it was opened in 1981 by Bob and Anne – Rudyard Kipling featured the area in The Jungle Books, although he never actually went there.

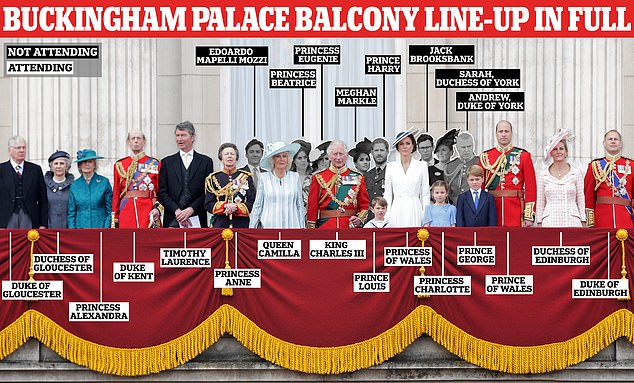

It has been the home for the past 35 years of Tara, an elephant made famous by Mark Shand, the late brother of King Charles’ wife Queen Camilla, in his book “Travels on My Elephant”. Shand gifted Tara to the Wright family in 1988 after his 600-mile journey across India.

After the death of her husband, Anne lived partly in Delhi, where she was still breeding race horses, and Kipling Camp where she died.

There will no doubt be memorial services elsewhere that reflect her life and achievements but, the night following her death, after a brief Christian service in Hindi, she was cremated in a small, open-sided village cremation shed in the jungle, a few yards from the park alongside a burbling stream. Those present, says Belinda, included camp staff, past and present, local friends and villagers who knew her well, along with their two faithful dogs. “As we left the Camp there were alarm calls nearby , and the place was crowded with cheetal deer when we returned”. A suitable exit for such a courageous wildlife campaigner whose death marks the end of an era.

Anne Wright is survived by a son Rupert and his children Helena and Tim, and her daughter Belinda.

A slightly shorter version of this obituary appeared in the Daily Telegraph on October 28, 2023 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2023/10/27/anne-wright-wildlife-campaigner-india-died-obituary/

Recent Comments