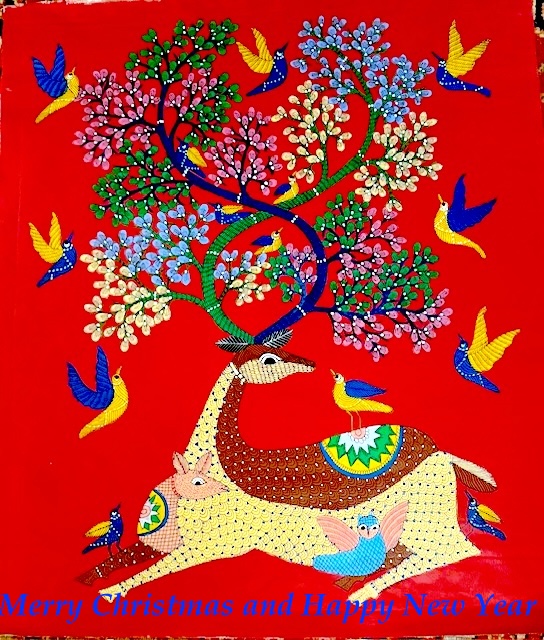

To all friends and followers of this blog, Seasons Greetings and all best wishes for 2026 – with this splendid painting by Jabbu, a Gond tribal artist from the Indian State of Madhya Pradesh

To all friends and followers of this blog, Seasons Greetings and all best wishes for 2026 – with this splendid painting by Jabbu, a Gond tribal artist from the Indian State of Madhya Pradesh

Posted in India

Modi and Putin praise each other and the India-Russia relationship

UK France and German ambassadors write in Times of India against Ukraine war

It could have been a tightrope walk, but President Vladimir Putin’s state visit to India during the past two days was so well stage-managed that it was a success both for him and prime minister Narendra Modi. Putin was showing the world that he could still be treated as a global statesman by a significant world power despite the invasion of Ukraine, and Modi was showing Donald Trump that he had alternative powerful friends to the US president. Together, they were giving a signal to the West of a signficant play in global politics.

The display of personal bonhomie began the moment Putin landed in Delhi on Thursday evening and shared Modi’s car to a private dinner. That led on Friday to the best pageantry and hospitality that India could provide, along with joint public statements and a mass of well-meaning agreements with a target set last year of $100bn trade by 2030.

While the visit only lasted just over 24 hours, it was one of the most significant and high profile of the two countries’ 23 annual summits and it gave much-needed fresh impetus to the relationship. But it was knocked off what would have been wall-to-wall television news coverage by pandemonium at India’s airports when over a thousand airline flights were cancelled due to operational problems.

The agreements aimed at developing economic and business ties to expand the relationship beyond its current defence and energy focus. But they did not go so far as Putin might have hoped.

They did not commit India to continue buying controversial Russian oil, which is being significantly reduced having mushroomed after the Ukraine invasion when it caused a rift between India and the US. Nor did they include major new orders for Russia’s S-400 missile defence system, which India is already using, nor joint production in India of Sukhoi Su-57 fifth generation jet fighters. That has given Trump less to complain about at a time when India is trying to finalise a US trade deal.

The annual summit is usually a bilateral event of only modest international significance. If Trump had not upset 25 years of work by successive US leaders coaxing India gradually to move away from its historic Soviet and Russian allegiances, it would probably not have hit the world headlines this week, apart from the focus on Ukraine.

But Trump’s imposition of 50% tariffs in July, coupled with criticisms of the Modi regime for buying Russian oil, upset that and led to Modi showing that he could be as close to Putin as he was to Trump in the past.

The visit could have turned into a trilateral with Trump interrupting from the US as a social media interloper but he has – so far – remained uncharacteristically silent. (He spent part of yesterday receiving FIFA’s surprise first Peace Prize at the World Cup draw in Washington). That has led to speculation that he knows he cannot now object to Modi being close to Putin when he is trying to negotiate a Ukraine peace settlement with business overtones. There are also signs of the US reaffirming its support for India’s role internationally.

Also in Modi’s and Putin’s minds would have been Xi Jinping, China’s president, who has been developing close links with Russia and is also patching up relationships with India after years of tense and sometimes hostile engagements on their undefined border. Modi has to be suspicious of Putin’s relationship with Xi, especially since China provides India’s hostile neighbour Pakistan with aircraft, missiles and other support.

Putin’s last visit to Delhi was four years ago this week during the covid crisis, two months before he launched the invasion of Ukraine. The visit lasted just five hours. Since then, he and Modi have had a total of 16 conversations, 11 between 2022 and 2024 five times this year.

At a regional summit in China on September 1, Putin ostentatiously invited Modi into his limousine for an hour’s private conversation. Modi said that “even in the most difficult circumstances India and Russia have walked together, shoulder to shoulder. Our close co-operation is important not just to our two countries but for global peace, stability and prosperity”.

Continuing the upbeat emphasis on the relationship, a detailed Indian government statement issued on December 4 described Russia as a “longstanding and time-tested partner” and said the countries had a “Special and Privileged Bond”.

Putin said in a long 100-minute interview with India Today tv before he left Moscow that Modi was “a person of integrity” who was “very sincere” about “strengthening Indian Russian ties across the whole range of areas, especially crucial issues of economy and defence and humanitarian cooperation, development of hi-tech”.

“It is very interesting to meet with him,” Putin added. “He travelled here, and we sat with him at my residence and we drank tea for the whole evening, and we discussed different topics. We simply had an interesting conversation purely like humans…. The Indian people can certainly take pride in their leader”.

Putin also said Russia was “a reliable supplier of oil” to India and was “ready to provide uninterrupted fuel supplies”. The US had continued to buy nuclear fuel from Russia so “why shouldn’t India have the same privilege!”.

At a joint media conference however, Modi said energy security had been a “strong and vital pillar of the India‑Russia partnership”, but avoided the oil purchases and defence deals. Instead, he mentioned the value of the two countries’ long-standing “win-win” co-operation in civil nuclear energy which they would continue to take forward”.

A major focus was on bilateral trade which rose sharply with the oil purchases to a record high of $68.7bn in 2024-25. That was made up by Russia’s (mainly oil) exports of $63.8bn while India’s totalled just $4.9bn. Putin was accompanied by a large business delegation, partly aimed to boosting what Russia buys from India. An India pharmaceutical factory in Russia plus investments in shipbuilding and critical minerals with encouragement for labour mobility and tourism are among the plans and proposals.

Perhaps the most unconventional and controversial diplomatic incident was an article written jointly by the British high commissioner in Delhi and the French and German ambassadors that was published on December 1 in theTimes of India. Titled “Russia doesn’t seem serious about peace”, it said: “Every day sees new indiscriminate Russian attacks in this illegal war, targeting civilian infrastructure, destroying homes, hospitals, and schools. These are not the actions of someone that is serious about peace”.

It is far from clear what the three countries’ ambassadors hoped to achieve, nor who they were trying to influence. They were rebuked by India’s foreign ministry for breaching “acceptable diplomatic practice”, and the Russian ambassador wrote a reply titled “Europe’s Four Treacheries are Impeding Peace in Ukraine”.

The high commissioner’s and ambassadors’ article presumably reflected the view in Europe that it was unacceptable for Modi to lay on such an unconditionally splendid welcome when Russia is not only failing to negotiate a Ukraine peace deal but is also provoking European countries with military and cyber space manoeuvres. Coincidentally, as he flew into Delhi, Putin was personally blamed by a UK inquiry for the death in 2018 of a Salisbury resident accidentally infected by the Novichok nerve agent intended to kill a former Russian spy and UK double agent. There were also reports of the UK unfreezing £8bn of frozen Russian assets to aid Ukraine.

Viewed however from Asia, which broadly regards Russia’s war with Ukraine as a distant problem for the West to deal with, Modi properly called for a peaceful solution, while Putin in his India Today tv interview mixed support for seeking resolution to the war with a hard line on winning the bitterly disputed Donbas region.

“We will finish it when we achieve the goals set at the beginning of the special military operation – when we free these territories”, Putin said, having just mentioned the Donbas when asked for his red lines. “Either we take back these territories by force, or eventually Ukrainian troops withdraw and stop killing people there”.

Authorities investigating Kashmiri bomb attack in Delhi

BJP coalition win in Bihar strengthens Modi’s authority

Narendra Modi’s authority as India’s prime minister has been significantly strengthened by an unexpectedly massive win for his Bharatiya Janata Party’s coalition in the Bihar state elections at a time when he has to deal with relations with Pakistan that are at a tense and terror-related pivotal moment.

Modi’s National Democratic Alliance won 202 of the Bihar assembly’s 243 seats, up from just 125 in 2020 in results announced on November 14. The BJP topped the polls with 89 seats followed by the state-based Janta Dal (United) with 85. Nitish Kumar, the widely respected but ailing 74-year old leader of the JDU, who has been chief minister of this desperately poor state almost continuously since 2005, is to remain in the post.

The special significance of this victory is that Modi does not need to distract attention and restore support for the BJP. It could have been different if his authority had been weakened by a defeat or marginal result in Bihar.

Modi is grappling with how to respond to a massive car bomb explosion near the Red Fort in old Delhi on November 10 that killed 13 people. Earlier this year in April, after a Pakistan-linked terrorist attack at Pahalgam in Kashmir that slaughtered 26 tourists and led to four-days of air-borne battles between the two countries, Modi said any future terror-induced incident would be treated as “an act of war”.

Modi and his National Investigation Agency (NIA) now have to decide whether the November 10 explosion was instigated, encouraged or facilitated by Pakistan. No organisation has claimed responsibility and Pakistan denies involvement, but Indian security sources are pointing to the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) that has close ties to the Pakistan military and the ISI security agency.

At the same time, Pakistan is accusing India of staging “state terrorism” with a suicide bombing that killed at least 12 people in the capital of Islamabad a day after the Delhi blast. India denies responsibility but the link stems from officials blaming the Pakistani Taliban (TTP), which is allied to the Afghanistan’s Taliban government at a time when it has been growing close to India.

The Indian government has confirmed it is treating the Delhi blast as a “terror incident” perpetrated by “anti-national forces”. Modi has described it as a “conspiracy” and Amit Shah, the home minister, said he would “hunt down each and every culprit behind this incident”.

This is complicated however because, unlike the earlier terror attackers who came from Pakistan, last week’s explosion involved Indian nationals from Kashmir. Claimed by Pakistan, Kashmir has suffered varying degrees of internally and externally instigated insurgency and terrorism since India’s independence in 1947.

Indian investigators have linked the blast to what they describe as “an interstate and transnational terror module” that they started tracking last month when posters promoting the JeM appeared in Nowgam, a village south of Srinagar that is at the centre of the disputed Kashmir territory.

Seven people were arrested including two Kashmiri doctors working in other Indian states. Police said they had uncovered 2,900kg of highly volatile explosives equipment and assault rifles in Faridabad near Delhi, which they now believe were being readied by the doctors and their accomplices for attacks on various targets. They have described the network as a “white-collar ecosystem involving radicalised professionals and students in contact with foreign handlers operating from Pakistan and other countries”.

The apparent emergence of such a terror group comprising professionals, and especially doctors who are widely trusted in security situations, has caused serious concern, though the radicalisation of white-collar groups has been seen before in Kashmir and elsewhere.

Complicating and delaying the investigation, the explosives seized in Faridabad were controversially transported 800 kms by mini-trucks to the police station in Nowgam for forensic examination. During handling, some of the volatile materials exploded on the night of November 14, killing nine people including police and forensic staff, and demolishing part of the police station. Officials say this was an accident, not an attack.

While the evidence may seem to point to Pakistan’s involvement, Modi has other issues to consider, notably a change in the triangular India-US-Pakistan relationship. In the past, India could assume that it would broadly have tacit US support for an attack on Pakistan after a terrorist incident, but that is no longer certain.

President Trump has become close to Pakistan’s army chief, Field Marshal Asim Munir (above), who is being given additional charge of the navy and air force as well as the security forces. This seems to involve powers approaching those of a military dictator, albeit within a (army dominated) parliamentary system. On November 11 Munir was also granted life-long legal immunity by the parliament.

Trump has entertained Munir twice at the White House and described him as “my favourite field marshal”. This coincided with Trump’s previous close relations with Modi being upset by the Indian prime minister rejecting his claims that he brokered the end of the April four-day battle between the two nuclear powers. India is never willing to accept outside interference in its relations with Pakistan and Modi has repeatedly rejected Trump’s claims.

Trump also imposed 50% tariffs on India after talks on a trade deal floundered, and India continued to be a major buyer of Russian oil despite the Ukraine war. Those issues have now eased, with Trump saying the oil purchases have declined and a trade deal is near.

Trump continues to call Modi a “great friend”, and relations between the two countries remain stable across a range of issues. But if he were to consider an attack on Pakistan, Modi would have to be wary of Trump’s reactions and be ready for the American president to be swayed by Munir. He also has to remember that the April battles led to serious though unconfirmed aircraft losses by India as well as Pakistan.

In Bihar, it always seemed likely that Modi’s NDA would win, but not by such a massive majority, routing the opposition including the Indian National Congress that won only five seats after alleging widespread election manipulation.

In addition to the pull of the BJP, the result is significantly due to the charisma and political experience of Nitish Kumar who authorised payments just before voting took place of Rs10,000 (£85) into the bank accounts of almost 15m women to start small ventures.

That is despite what a visiting American commentator has written in the FT , maybe unfairly, about Kumar having “more obvious infirmities than Biden”. An Indian Express columnist has written that “the NDA’s landslide win in Bihar was, above all, about Nitish Kumar and Biharis’ ‘sahanubhuti (sympathy)’ for their leader and what many said was ‘shraddha (respect)’ for his stewardship over the last two decades”.

The BJP’s success is the latest of a series of significant state assembly victories in Haryana, Maharashtra, and Delhi following a mediocre general election result last year. Together with its NDA allies, it is in power in 21 of India’s 31 states and union territories. Modi has said his next target, early in 2026, is West Bengal where the BJP has previously failed to oust the state-based Trinamool Congress.

Christie’s score classical art records with Aga Khan family auction

Mrinalini Mukherjee is first Indian to have a show at the RA since 1982

Two events in London last week illustrate Indian art’s growing importance, both for moneyed collectors and for galleries and museums. Just as previews were starting on October 28 at the Royal Academy of Arts in Piccadilly for a much-heralded exhibition of works by renowned sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee and her fellow artists, one of the most striking auctions for years was hitting record prices a few hundred yards away at Christie’s.

Bids were flowing for 95 classical Indian and Islamic works from the personal collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan, part of the family of the Ismaili Muslim sect’s spiritual leader. Records were broken with sales totalling £45.76m.

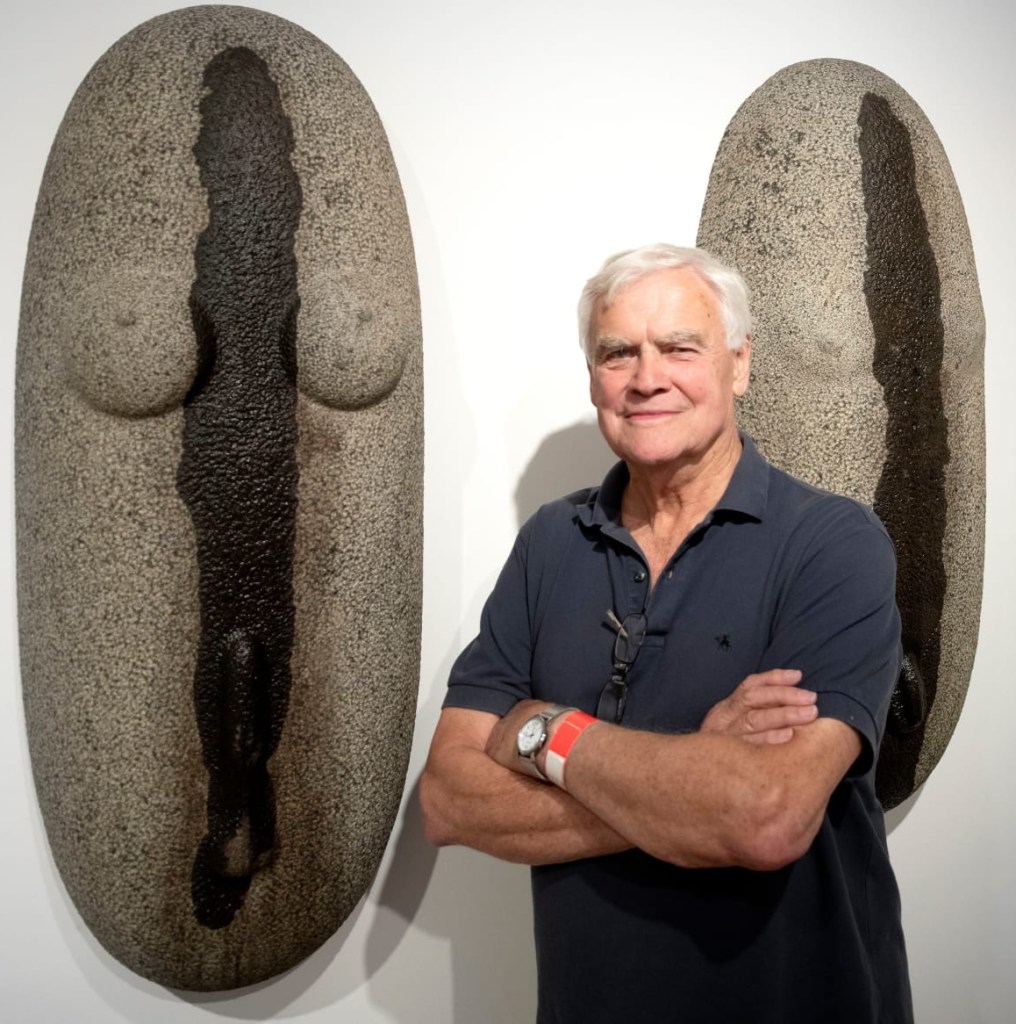

At the Royal Academy (RA), the most striking work on show was Pakshi, Mukherjee’s iconic 7ft high suspended sculpture (left) of voluminous golden-brown to pinkish red knotted hemp resembling both a deity and a human figure.

At Christie’s, headlines were grabbed for a 12in x 7in painting on cloth of a “family of cheetahs in a rocky landscape” (below), attributed between 1575 and 1580 to Basawan, a famous Indian Mughal artist who was said to have been a favourite of Emperor Akbar.

This established a record for a classical Indian or Islamic painting with a hammer price of £8.5m ($11.16m), an astonishing twelve times the low estimate, and £10.25m including fees.

The works were mostly acquired by Sadruddin and his wife between the 1960s and 1980s, and the sale attracted buyers who have been setting new records this year for 20th and 21st century modern Indian art as well as museums and other collectors from the Middle East and elsewhere. The £45.76m ($60m) total beat the top South Asian art auction record of $40.2m achieved at a Mumbai-based Saffronart sale of modern works on September 27.

“This was a once in a lifetime opportunity to acquire very famous paintings from a highly illustrious collection,” says Hugo Weihe, an independent Indian art advisor. The prices achieved for the many relatively small paintings showed “that it is not always about size, but artistic merit and appreciating the full scope of cultural heritage.”

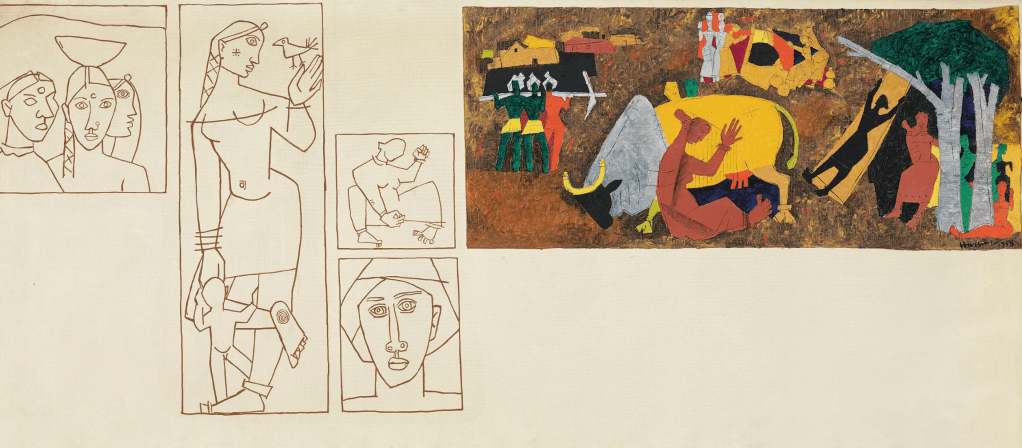

The overall sale was Christie’s second significant coup within a few months. It lagged behind other auction houses during the South Asia summer sales, but in March it achieved the highest auction price ever for an Indian painting – M.F. Husain’s 1954 Gram Yatra, which sold for $13.75m.

Mukherjee’s RA show, which continues till next February, is significant both for the artist and for Indian modern art at a time when international attention is growing with the high auction prices and increasing institutional interest in staging exhibitions.

This is the first exhibition of Indian modern art at the Royal Academy since the 1982 Festival of India in the UK that was driven by the then prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and Indira Gandhi. Benefitting from the political focus, it involved works by 45 artists in the main large galleries (currently occupied by a stunningly dramatic and colourful exhibition of the American artist Kerry James Marshall). With works by seven artists, the Mukherjee exhibition is located on one of the academy’s upper floors.

Mukherjee’s last UK show was some 30 years ago in Oxford, though she had an acclaimed exhibition titled Phenomenal Nature at New York’s Met Breuer gallery in 2019. Pakshi was among her “deities” shown at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

With almost 100 works spanning a century, the RA exhibition flows on from a modern art show at London’s Barbican last year, which had a tighter-focussed 1975-98 time span with over 150 works by 30 artists, including Mukherjee and several others who are at the RA.

Sadly, there are on show only a few of Mukherjee’s spellbinding large textile figures like Pakshi for which she is most famous. This is partly because of financial constraints and partly because of what the RA describes as conservation issues with transporting older hemp works (though more have appeared at other exhibitions).

Mukherjee’s other bronze and ceramic sculptures along with water colours are also on show, accompanied by works by her mother Leela (left) and five other artists who were friends and who influenced each other’s styles. A very high proportion of the works have not been shown abroad before, including those by her mother.

The friends include husband and wife Gulammohammed (GM) and Nilima Sheikh. GM Sheikh had a memorable retrospective in Delhi early this year and both were included in the Barbican exhibition. Nilima has a softly colourful installation of hanging vertical scrolls (below) not previously seen outside India, Titled Songspace, it uses milk-based casein protein to bind the paint pigments. Other notable works include paintings by Jagdish Swaminathan and K.G. Subramanian.

The RA says that the main aim has been to show the close relationships and shared learning and support between the artists. This formed a “vibrant creative and intellectual network that influenced the development of modern and contemporary art in South Asia”.

As one of the oldest art schools in Europe, the RA highlights India’s notable art institutions—the Kala Bhavana (Institute of Fine Arts) in Santiniketan, founded in 1919 by the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, and the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda, which are both noted for their artistic learning and styles. They comprise two of the sections of the exhibition, the third being Delhi.

Notably not included, because they are not relevant to the Mukherjee story, are the Mumbai-based Progressives such as M.F. Husain and F.N. Souza who date from the 1940s and dominate the top end of the auction market.

Mukherjee’s most memorable exhibition, Transfigurations, opened in Delhi’s National Gallery of Modern Art just a week before she died in 2015, aged 65. The gallery’s vast spaces were filled with her large and striking textile sculptures as well as metal and other works. I walked through that exhibition with the curator, Peter Nagy of Delhi’s Nature Morte Gallery, and wish I had written about it then.

Tarini Malik, now the Royal Academy’s chief curator for modern art, was also there and met Mukherjee before the artist died. That gave her the ambition to stage what is now on view at the RA, while acknowledging that the show should have been done years ago.

The RA covers the theme of Mukherjee and friends well, with neat division into the three Santiniketan, Baroda and Delhi parts. For many, it is a welcome opportunity to see so many works by respected names that have been loaned from normally hidden private collections. But unfortunately this is neither an exceptional display of a century of Indian modern art, nor an adequate display of Mukherjee’s drama.

Reviews in the UK media so far have been partly critical, reflecting the absence of enough of Mukherjee’s big textile work and the remoteness of the basic theme. The FT tactfully ends a generously positive full page-spread with “the contextual lacunas make this seem more a show, perhaps, for the initiated connoisseur”.

The Guardian is most belligerently negative. After saying Mukherjee’s “surreal spins on Indian folk and sacred art are powerfully fascinating”, it asks why the RA has tried “to suffocate her exhilarating works in an incoherent show that surrounds them with mediocre stuff by much less interesting artists”.

The Times reviewer says, “In many ways, it’s a beautiful show, aided by soft lighting and pale-pink walls. But I can’t help but wonder whether it would have been better off as a family affair.”

This is not the end of the story. Tarini Malik will be curating a follow-on exhibition next May at the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield that describes Mukherjee as “one of the world’s most significant modernist sculptors”. The gallery website says this will be a major Mukherjee retrospective, but it seems that it will also include her mother Leela along with sculptures by other female artists. The critics hope that the focus will be clearer than many see it at the RA.

Posted in India | Tags: art, christies-record, exhibitions, history, Mrinalini Mukherjee, painting, royal-academy-indian-art, travel

Many accidents of history in Imperial India’s five Partitions

Indian empire stretched from Aden and other Arab States to Burma

Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia by Sam Dalrymple – UK: William Collins, London, £25 hardback, India: Harper Collins India, New Delhi, Rs799 hardback 528 pages

For most people, even those well versed in colonial history, the word “partition” mainly conjures up images of the hundreds of thousands of Muslims and Hindus who were killed in 1947 fleeing between northern India and Pakistan at the time of independence from Britain. Little is even remembered about similar crossings in the east between what is now West Bengal and Bangladesh.

Sam Dalrymple explores these events in detail in his book Shattered Lands and then goes on to break important new ground by taking the story much further to include Imperial India’s little-known total of five partitions. Delhi’s writ stretched from the Indian Subcontinent across the Arabian Sea to what is now Yemen, Oman, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait. That was in addition to India’s neighbours Burma (Myanmar) and the somewhat reluctant protectorates of Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim.

The Indian Raj “housed a quarter of the world’s population and was governed by the Indian rupee”, says Dalrymple. He has left out Afghanistan that never became part of the empire, even though Britain fought several wars there and controlled its foreign policy for 40 years.

The Arab states bordering the Ottoman Empire, we learn, were usually left off Imperial maps to avoid annoying Constantinople, while Nepal and Oman never officially recognised their protectorate status. Yet they were all legally part of “India” – run by the Indian Political Service and subservient to the Viceroy of India. Defended by the Indian Army, they paid Indian taxes with Indian rupees.

That establishes the contours that Dalrymple has devised for this wide-ranging book which shows how haphazardly many historically significant decisions were taken. Some were hurried with almost random implementation, creating problems that remain today – notably trouble-torn Kashmir that is divided and claimed by both India and Pakistan. Some claims for partition were rejected – Nagaland has never fully accepted being a state in north-east India and could have become part of Burma (Myanmar).

The partitions began in 1937 when Burma was separated from India as a crown colony to meet anti Hindu-India nationalist demands and enable London to establish direct links separate from Delhi. Also, that year, the separation of Aden began the Arabian Peninsula partitions that continued till the Persian Gulf states went in 1947.

India’s political leaders did not oppose losing the (Muslim) Gulf states and Dalrymple describes this as “India’s greatest lost opportunity” because of the oil wealth that was discovered later. But for these partitions, he says, the countries “might have become part of India or Pakistan after independence”. That however is surely a most improbable “what if….”, not least because of the unreality of expecting those Muslim nations to accept life run from Hindu India.

The bloody creation of Pakistan in 1947 came next, which Dalrymple presents as an idea that flowed from the partitions of Burma and Aden. After years of discussions Jawaharlal Nehru, who was about to become independent India’s first prime minister, admitted “we are tired men” and said the plan for partition “offered a way out and we took it”. Dalrymple however does not adequately blame Nehru for killing off an earlier “way out”. In a July 1946 speech, he had refused to honour what was known as the widely accepted “Cabinet Mission” plan for a federal set-up, which would have avoided the violent partition and all that followed.

Next came the fourth partition when the new Indian government headed by Nehru and his tough Home Minister, Sardar Patel, virtually instructed India’s 562 princely states to cede to Delhi. Britain had only directly ruled 60% of the Indian land mass. The rest belonged to these states that were independent, up to a point. They were subordinate to the British crown in foreign policy, defence, and communications, and their maharajas and lesser princely rulers were subject to advice from an often-interfering British Residents (political agents).

Nehru and Patel never recognised them as having any right to independence, but they were less committed about the kingdoms of Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim, which had varying treaties with the British raj. Nehru was sympathetic to their Himalayan identity, and they were left off the list. Nepal became a sovereign nation, and Bhutan and Sikkim kept special independent status. (Indira Gandhi annexed Sikkim in the mid-1970s, and China is now trying to undermine Bhutan’s friendship treaty with India,).

As the empire gradually “shattered”, some colonies became republics, cutting all links with Britain, while others settled for dominion status and became part of the Commonwealth, which later also admitted republican India and others. Dalrymple sadly does not deal with this aspect of international affairs. That may be because he focuses on the gradual decline of empire, rather than tracking later institutions, though the idea of the Commonwealth goes back to the 1880s.

Within the Indian subcontinent, the colonies of Pakistan (with Bangladesh hived off in 1971 as Dalrymple’s fifth partition) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) did join the Commonwealth, but Nepal and Bhutan did not because they prized their independence. Neither did Burma. The Gulf states were technically eligible but chose the regional Gulf Co-operation Council that was set up in 1981. That was in line with earlier opt-outs by Palestine and others in the region, though Palestine and Yemen did apply for membership in 1997 without any decision. (Palestine’s case and the role of the Commonwealth is now being informally discussed (see this link) at a time of growing international support for its statehood).

Dalrymple vividly covers the collapse of British rule in the Gulf once these countries had lost their role in the Indian raj, and an energised Arab nationalism clashed with fading British imperialism. After almost coming to hostilities, there is the Sultan of Oman’s $3m sale of the important Arabian Sea port city of Gwadar to Pakistan in 1958. The Sultan held the city that lay on the Pakistani coast under a 1783 treaty. (Gwadar, in Balochistan province, is now a key nautical link in the Pakistan leg of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and a centre for Baloch nationalist opposition to rule from Islamabad).

Significantly, Dalrymple shows how the current India government’s Hindutva focus has roots from these years when the British tacitly agreed that “India belonged primarily to the Hindus” and hived off the largely non-Hindu parts. Hindu nationalism “was a key driving force in those earlier partitions” of Burma and Aden as well as the later divide of India and Pakistan.

As he weaves his way through this history Dalrymple introduces gems that would not be picked up by most historians. Tracking the rise of Abdel Nasser as Egypt’s president, and the beginning of the Arab oil boom just a few years after Britain’s departure, we hear about Dhirubhai Ambani, father of Mukesh who is now one of Asia’s richest men, arriving in Aden from Gujarat. He was 17 and was soon managing ship refuelling for A. Besse & Co., a French trading firm. As Nasser took over the Suez Canal and Arab nationalism became more violent, Ambani returned to Gujarat at the end of 1957 with his wife and eight-month-old Mukesh to found what became Reliance, now India’s biggest conglomerate.

On a different wavelength, we hear early in the book about the “open marriage” of “pretty Dickie” Lord Louis Mountbatten, Britain’s last Viceroy, and his wife Edwina. Her most widely researched and analysed relationship was with Nehru, which had “raised many eyebrows” within just ten days of the Mountbattens arriving in Delhi in March 1947. Later, when writing about the Nagaland people’s call for independence in north-east India, Dalrymple has an aside that mentions Edwina again, just after logging Indira Gandhi’s alleged affair with a possible CIA plant in Nehru’s office. Watching Naga dancers in Delhi, just two weeks before she died, Edwina exclaimed to a friend, “Don’t they have beautiful bottoms!”.

Such light-hearted references add to this magnificent (and massive) first book by Sam Dalrymple. It misses out or underplays one or two turning points; and could have usefully included the evolution of the Commonwealth. But it does add a new perspective to the region’s history, and the accidents of history, covering a wide canvas with an appealing writing style that makes for compelling reading.

Since he is the son of author and historian William Dalrymple, many of whose books explore the Indian Raj, there is inevitable curiosity about family involvement. Sam told The Indian Express that the book began as a documentary project with National Geographic until Covid prevented filming. His father then suggested turning it into a book, and read the first and final drafts, but his mother, the artist Olivia Fraser, was “the real editor-in-chief, reading everything meticulously”.

This is an expanded version of a Book Review published by Taylor & Francis in “The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs and Policy Studies” on October 15, 2025, available at https://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/D42SVVFYPANTHT3ITTNY/full?target=10.1080/00358533.2025.2568597

Posted in India | Tags: Commonwealth India, Dalrymple India, Dalrymple Nehru, Edwina Mountbatten, Five Partitions, history, Imperial India, India, India Aden, India books, India Kuwait, India partitions, Indian empire, Mukesh Ambani, Olivia Fraser, Pakistan, Sam Dalrymple book, Shattered Lands review, The British Empire 1921, William Dalrymple

Saffronart hits $40m for a single auction

Indian art galleries on show in London’s Frieze exhibitions

There’s a boom in the modern Indian art market with sales recently totalling £96.2m at international auctions in a period of under two weeks, and with a significant number of Indian galleries showing at the Frieze London and Masters exhibitions in the UK capital this month.

The strong prices have revived memories of the first boom in 2005, which was partly triggered by newly-rich Indian buyers working in New York financial services. That fell away with the 2008 financial crisis. This time, the boom has a stronger base, leading to 10 or more galleries showing at the Frieze exhibitions. There are many new buyers of all ages, even though the boom is partly fueled by individual collectors competing for the top lots.

“Indian art is now being accepted as an asset, like gold or real estate, that you buy and hold because of its long-term value, rather than trading,” said Dinesh Vazirani, who founded the Saffronart gallery with his wife Minal in 2000.

Leading the sales, Saffronart almost doubled the maximum total for an Indian auction to $40.2m, while Sotheby’s and Pundole each totalled $25.5m and $18.3m with Christie’s trailing at $12.4m. All four were celebrated as “white glove” sales, where all the lots were sold.

Top prices were achieved for a variety of artists. They were inevitably led by members of the ultra-safe Bombay-based Progressives Group, which began in the 1940s, with names such as F.N. Souza, M.F. Husain and V.S. Gaitonde. Records were also set however for later artists including Bhupen Khakhar, Mohan Samant, Arpita Singh Vivan Sundaram and Nalini Malani who have been attracting increasing interest at auctions, though there were few works from contemporary artists.

Competition between two top collectors helped to boost prices for some prime lots, notably at Sotheby’s auction in London on September 30 where Manjari Sihare-Sutin, co-head of South Asian art, said the £18.9m ($25.5m with premium) achieved was the department’s highest total in its 30-year history.

Two Souza works created a new record for the artist after a contest between Shankh Mitra from the US, who is a relatively fresh collector and was in the auction room, and Kiran Nadar who bids down the telephone for her large art museum in Delhi.

Bidding against Mitra, Nadar won the Emperor at a hammer price of £4.2m, ($6.9m with premium), beating the artist’s previous $4.89m record set at Christies in New York in March 2024.

A few lots later, in another tussle that began with nine bidders, Mitra set a higher record with Houses in Hampstead (above) at £4.6m ($7.57m with premium). This followed a Christie’s New York contest between th two collectors last March for a notable Husain work that Nadar eventually won for $13.75m. Mitra has also been buying extensively in other auctions, challenging Nadar’s success for many years at acquiring the best works by top artists. He is the ceo and chief investment officer of Welltower Inc, a real estate investment trust working in the healthcare sector.

A comparable Souza Belsize Park, London, 1961 is coming up in an on-line auction at London-based Roseberys auctioneers on October 24. It is a little under half the size of House in Hampstead , so could get bids far far above the unrealistically modest £15,000 ($20,000) top estimate.

Another Souza record came in the Saffronart sale on September 27 in Delhi for a unique collection (above) of six 10in x 8in pen and ink on paper drawings titled Six Gentlemen of our Times. This sold for an unexpectedly high hammer price of Rs170m ($2.30m including 20% buyers’ premium), which was the highest auction price ever paid for a South Asian work on paper.

Delhi-based art critic Geeta Kapur has described these heads as “a combined portrait of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, sly, evil and at the same time terrified.” The next lot was a similar single man’s head by Souza. It went even more surprisingly at a hammer price six times the top estimate for the rupee equivalent of $67,797 (including the premium).

All four auction houses pitched many of their estimates low – at Sotheby’s 94% of the lots exceeded their top estimate. The aim was to draw in bidders at a time when art is being increasingly seen in India as a strong investment, pulling in new collectors – a third of Sotheby’s buyers were new to the auction house.

In celebration of its 25th anniversary, Saffronart packed its 85-lot auction so successfully with top priced works that the leading ten lots alone went for a total of over £25m. The total $40.2m beat a $25.2m all-India record that Saffronart set in April.

The low estimates brought some remarkable multiples.

Pundole’s Rs1.62m ($18.29m) auction of 81 lots on September 25 in Mumbai had a dramatic start with memorable early works by members of the Progressives Group, all painted when they were in their 20s. They were part of a collection assembled by Emanuel Schlesinger, an Austrian emigre who fled from Europe in the 1930s to escape Nazism and became a patron of young Bombay artists.

A figurative 32in x 31in oil on canvas, Morning Bath, by M.F. Husain (above) fetched eight times the top estimate at a hammer price of Rs190m – $2.46m including Pundole’s 15% buyers’ premium. Three watercolour landscapes by S.H. Raza included a 12in x 18.5in panoramic view across Bombay’s Marine Drive and city from Malabar Hill (above) that went for 14 times the top estimate at a hammer price of Rs22m ($248,000 including premium).

Works by Mohan Samant, a lesser-known member of the group, who mostly lived in New York, had several successes with a personal record of Rs5.5m ($62,000) hammer price, seven times the top estimate, for a 33in x 27in watercolour, Red Carpet.

“We saw increasing emphasis on artists outside the more predictable names,” says Dadiba Pundole. “Collectors are also more aware of works of academic importance, and are willing to fight for these, irrespective of medium or scale.”

Arpita Singh’s record came in at Rs165m ($2.14m with premium) at the Pundole auction for a colourful 68in x 68in oil on canvas titled With and Without Shadows (above). The veteran artist had a highly successful retrospective exhibition in London during the summer, which brought fresh attention to her work.

Pundole’s top lot was a 45in x 36in oil on canvas by Tyeb Mehta depicting a female labourer from 1983. It sold for a hammer price of Rs260m ($3.37m including premium). Also in this auction, Bhupen Khakhar achieved a record work-on-paper price of Rs42m ($544,839 with premium) for an erotic gay form of puja, with the artist in the crowd.

Gaitonde’s record came in the Saffronart auction for a glowing gold coloured untitled 55in x 40in oil on canvas in the artist’s iconic misty style (right). This was an early work, painted in 1971, and it fetched a hammer price of Rs560m ($7.58m including the premium) exceeding Gaitonde’s previous record of Rs420m at a Pundole auction in 2022.

Bidding was slow for the top lots at Christie’s $12.34m auction on September 17 in New York where a V.S. Gaitonde achieved a top price (including premium) of $2.39m and a Tyeb Mehta Trussed Bull went for $2.03m.

By contrast, another work in Mehta’s Trussed Bull series was sold (to Shankh Mitra) for Rs470m ($6.37m including the premium) at Saffronart’s auction, following a record $7.2m set for a similar work at Saffronart in April.

Historic distrust of the US being revived as Trump raises US import tariffs up to 50%

Trump says India, buying Russian oil, “doesn’t care” how many Ukranians are killed

President Donald Trump’s decision on August 6 to raise tariffs to 50% on many Indian imported goods from the end of August has seriously undermined work pursued with India by four earlier US presidents, starting with Bill Clinton 25 years ago and continued by Trump himself till a few weeks ago, The task has been to coax India gradually to move away from its historic Soviet and Russian allegiances and build lasting links with the US and other Western powers.

Trump’s move, triggered by India becoming the biggest buyer of Russian oil since the Ukraine war began, is reawakening and strengthening India’s instinctive distrust of America. Calls are emerging for it to stand up to his demands to cut the oil purchases, “Resisting the US might cause short-term pain, but not doing so will hurt India’s national interests,” was the headline on an article by Shyam Saran a former foreign secretary, who describes Trump as “a nightmare”.

The presidents have all considered their approach necessary in order to develop India as a buffer against the growing power of China – despite a general understanding that, with its developing policies, initially of non-alignment and now multi-alignment, the world’s fourth largest economy was unlikely to come fully on-side with the West.

Good progress has been made by the US in terms of wide-ranging defence and other co-operation. Angry however that India is boosting Russia’s economy by buying its oil during the Ukraine war, Trump has disrupted the relationship along with his boosting trade tariffs first up to 25% and now to 50%. At the same time, he is sidling up to Pakistan and the country’s all-powerful army chief General Asim Munir as well as making aggressive remarks that are escalating the row.

The question now is whether this has done serious damage, not only to India-US relations but also to wider Indo-Pacific strategy, or whether it could be at least partially blown away once Trump’s battles with India over trade tariffs and Russian oil sales have been solved.

The extra 25% will come in to force on August 27, two days after trade talks planned, but not yet confirmed, to take place in New Delhi. It became clear on August 4 that Trump was not waiting for the talks to proceed because he had decided to make Russian oil his immediate goal. He has also said that there could be further secondary sanctions, which presumably could include electronics and pharmaceuticals that remain exempt for now.

India’s foreign ministry criticised the US tariffs “unfair, unjustified and unreasonable”. Its oil imports were “based on market factors and done with the overall objective of ensuring the energy security of 1.4bn people of India”. On tariffs, Modi said he would “never compromise on the interests of farmers, livestock owners and fishermen”.

Trump wrote on his Truth Social media platform on August 5: “India is not only buying massive amounts of Russian Oil, they are then, for much of the Oil purchased, selling it on the Open Market for big profits. They don’t care how many people in Ukraine are being killed by the Russian War Machine”.

That brought a quick uncompromising response from India, which Trump is targeting while not challenging China that is also a big oil purchaser. “The targeting of India is unjustified and unreasonable,” said Randhir Jaiswal, India’s foreign ministry spokesperson. “India began importing from Russia because traditional supplies were diverted to Europe after the outbreak of the [Ukraine] conflict, The United States at that time actively encouraged such imports for strengthening global energy markets stability.” India also alleges that the European Union and the US continue to actively trade with Russia in excess of India’s trade.

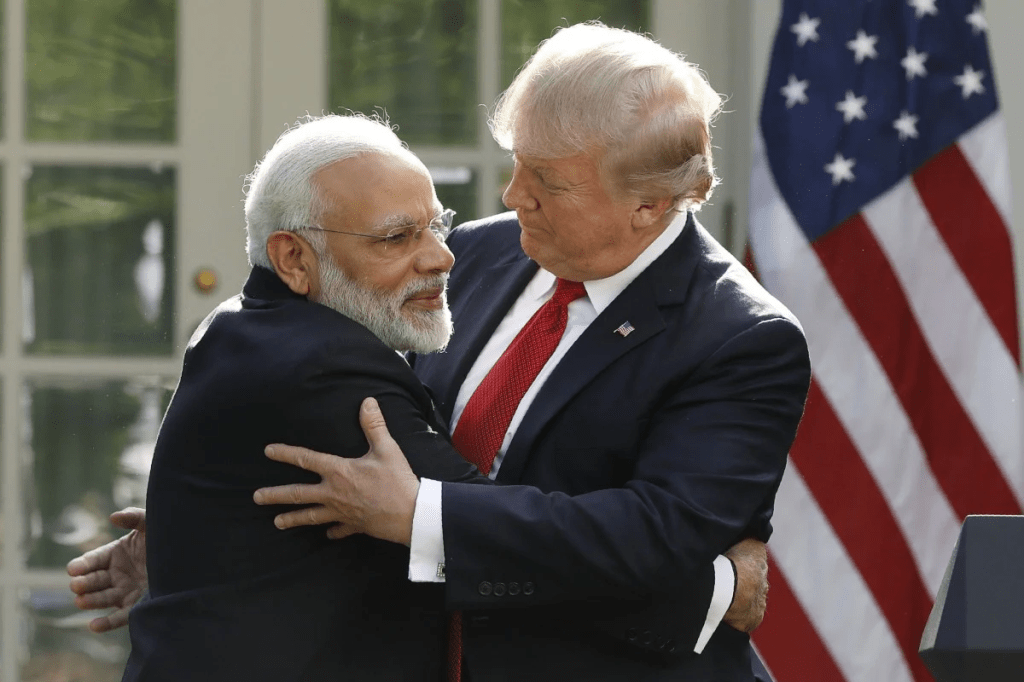

Prime minister Narendra Modi, who has flattered Trump at every opportunity, is inevitably undermined by his supposed international buddy suddenly turning on India. This was not expected, certainly not with the current persistent ferocity. The two leaders basked in triumphal joint “Howdy Modi” and “Namaste Trump” rallies when they visited each other’s countries in 2019 and 2020. When Trump was re-elected, there were signs that the close rapport would continue, even though his “America First” approach would lead to tougher trade demands.

One recent irritant in the relationship is that Trump seems unable to tolerate Modi and Indian officials persistently rebutting his repeated (and over-stated) claims that he personally ended the recent near-war between India and Pakistan. The US was involved in behind-the-scenes peace making along with other countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UK. India however is hypersensitive about outside interference in its Pakistan relations so resists Trump’s public claims.

Trump’s tirade began on July 30, when he announced that India’s imports would be hit with 25% tariffs from August 1, the deadline that had been set when he first announced (and then postponed) 26% tariffs on April 2, his trade war “liberation day” .

Trump is frustrated over what he sees as India’s slow moves on key tariffs, especially for US agricultural exports such as soya beans, dairy products and wheat where India’s import tariffs can reach as high as 40%. Trump’s electoral base needs access to these exports as well as other items where India has made concessions. But Modi cannot move far without upsetting farmers, many of whom are poor and make up 40% of the country’s workforce.

The Financial Times reports (Aug 5 print edition) that India was blindsided after it hired Jason Miller, a central Trump campaign adviser, to try to get the president’s ear: “New Delhi struggled to convince the US president it was doing enough to open its markets to US exporters. Each time Lutnick presented Trump with a new Indian proposal, the president sent him back to negotiate harder, people familiar with the matter said”. As the clock wound down, Trump launched his attack. (Miller has a chequered history).

Saying “India is our friend”, Trump then made his first threat of an additional undefined “penalty” because of the large oil and military equipment purchases from Russia.

“I don’t care what India does with Russia. They can take their dead economies down together, for all I care, their tariffs are too high, among the highest in the world,” he declared a day later in his late-night Truth Social posts, mixing the trade and oil issues. That hit international news headlines but, in typical Trump style, it ignored reality – India is a growing major world economy, its traded goods with the US totalled some $130bn in 2024, and the US is India’s largest trading partner.

The 25% tariffs were not a surprise. India had been preparing for trouble since a possible deal is said to have arrived on Trump’s desk a few days earlier. India’s official response has been that it is “studying the implications”, but ominously added it would “take all steps necessary to secure our national interest”. That seems maybe to have provoked Trump’s “dead economies” remark.

India’s role as the biggest purchaser of Russian oil is a key issue now that President Vladimir Putin is resisting Trump’s attempts to end the war with his imminent deadline of August 8. Since the war began, India has cited Russian low prices to justify increasing purchases that currently make up 35% of its total imports compared with 37% from Saudi Arabia and the UAE and 22% from Iraq. The US share has risen in response to Trump pressure from 3.5% in 2023-24 to 7.3% in April. Trump has said he will impose sanctions on Russia and countries that buy its oil including India and China if Putin does not agree to a ceasefire by August 8.

Stephen Miller, deputy chief of staff at the White House and one of Mr. Trump’s most influential aides, on August 4 warned that Trump had “said very clearly that it is not acceptable for India to continue financing this war by purchasing the oil from Russia.”

Trump had told reporters on August 1, “I understand that India is no longer going to be buying oil from Russia…. That’s what I heard. I don’t know if that’s right or not. That is a good step. We will see what happens.” The word from Delhi was that he was wrong. A climb down on buying from Russia indeed looks extremely difficult, given India’s robust stand on the issue so far. It does seem likely however that energy concessions will form part of the eventual trade deal, probably with India agreeing to step up its oil purchases from the US.

Oil has also figured in developing relationship between Trump and Pakistan, which has offered him an astonishing array of deals ranging from cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence to hydrocarbons and critical minerals – plus nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Asim Munir, Pakistan’s army chief, discussed trade and his country’s potential for mining bitcoin and exploring rare earth minerals in a surprise White House lunch last month that marked the beginning of the new relationship. Since then, Pakistan’s lobbying efforts have been stepped up in Washington, and it looks as if Trump has been hooked.

Last week Trump announced a deal with Pakistan to develop the country’s “massive oil reserves”. That surprised observers because Pakistan has only a low level of some 240m barrels. He even provocatively suggested Pakistan might one day “be selling oil to India”.

When he launched his tirade, Trump had just returned from a triumphal semi-private trip to Scotland, where he mixed visiting his two golf courses and opening a third with a visit from Sir Keir Starmer who flew with him in the presidential Air Force One passenger jet and helicopter. He also finalised an EU trade deal with Ursula von der Leyen, the European Council president who flew in from Brussels.

Gangster King Trump

That led Bill Emmott, former editor of The Economist, to dub Trump a “blend of gangster boss and Medieval king but adapted for our televisual age,” adding: “When the boss-king takes his court to Scotland, British and European leaders fly in to seek his favours, which he loves”.

Three days before Trump arrived, Modi had been feted on an official visit to the UK where he met King Charles as well as Starmer and signed an India trade deal. Maybe that provoked Trump to focus on what India had not negotiated with the US, tempting him to bring Modi down a peg or two.

In China, Xi Jinping is watching Trump’s moves against his large neighbour . Nothing that has happened so far will drive Delhi closer to Beijing, and it has many stable diplomatic and other links with the West, not least the Quad alliance with the US, Japan and Australia which is due to hold its annual summit in India later this year. There is also the BRICS grouping that Trump has decided to attack.

But even if the disputes over trade tariffs and oil purchase are resolved – and neither will be easy – Trump’s flirting with Pakistan will continue to make India unsure when dealing with unpredictable US presidents, now and in the future. It could also drive India back towards Russia, which is what all the presidents have been trying to stop for a quarter of a century.

Dramatic, though phased, reductions in tariffs plus other deals

Diplomatic significance that a Labour Government can work with India

LONDON: For decades India and the UK have eulogised about their common heritage, their shared values and common language, hoping a series of isolated initiatives based on good intentions would yield material results in terms of increased trade and investment partnership. But the dreams of future potential have never been fully realised, even though two-way trade has grown from some £3bn in the early 1990s to £43bn last year.

The signing of a multi-billion-dollar free trade agreement during Narendra Modi’s official visit to the UK this week (July 23-24) should gradually change that after the years of unrealised hopes. “Today marks a historic day in our bilateral relations,” Modi said during a signing ceremony at Chequers, the UK prime minister’s country residence. The aim is to double two-way trade to over £80bn ($112bn) by 2030.

After three years of tough negotiations, there are to be wide-ranging phased tariff reductions, though the deal still has to be approved by the UK parliament, which might delay implementation till next year. There is also fresh and expanded co-operation in other areas including visas plus defence, technological cooperation, education, climate and security.

Britain has signed recent trade deals with the US and the European Union, but prime minister Keir Starmer said at Chequers that the Indian deal was the “biggest and most economically significant” the UK has concluded since it left the European Union in 2020.

For India, it is the first major free trade pact outside Asia since it decided not to join the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2019.

The deal is significant diplomatically because it shows that Starmer has persuaded India that his Labour government is not shackled by the Labour Party’s historic pro-Pakistan stance over the disputed region of Kashmir and by over-riding sympathies for protests by minorities in the UK. Starmer has also approached the negotiations with a more determined workmanlike approach than Boris Johnson and other Conservative leaders.

Viewed from India, the deal is significant because it shows how Delhi is widening its bets now that its developing alignment with the US has been upset by President Donald Trump’s erratic style of government. Put more formally, the deal is in line with India’s foreign policy of multi-alignment.

Modi’s 24-hour visit

Modi was said to be on a two-day visit, but he was only in the UK for 24 hours and did not come to London. He stayed the night he arrived in a hotel near Luton where he was feted by members of the Indian community. He flew in and left from the capital’s third airport at Stansted in Norfolk, near the Sandringham country home of King Charles where he met the King at the end of the visit.

In between he was at Chequers, Keir Starmer’s country retreat not far from his hotel, where he also met businessmen and the Indian diaspora. This unusual avoidance of London meant there was no risk of the sort of mass demonstrations that greeted Modi on his first visit as prime Minister in 2015, when Parliament Square and surrounding streets were closed and barricaded.

Modi was far from popular at the time, mostly because of mass deaths in 2001 in Gujarat when he was chief minister. The Times ran a headline saying, “Hold your nose and shake Modi by the hand”, while The Guardian went over the top with “India is being ruled by the Hindu Taliban”.

But times have changed, and the world has moved on. Since he became prime minister in 2014, Modi has rebuilt India’s image internationally as the world’s fourth largest economy. He has also built his own image as an international, though still controversial, statesman. While his critics now focus on his government’s authoritarian and Muslim-restricting Hindu nationalism, the world’s focus is on how to boost and manage trade in an environment dominated by Trump’s unpredictable tariffs.

The Economist even said this week that the deal was “a rare win in the Wild West of global trade”, adding that “the global uncertainties of Mr Trump’s tariff vendettas make the pact stand out as an unusually well-negotiated and orderly way of boosting global trade.”

Moves towards an agreement began in 2021 but negotiations, which started a year later, failed to meet Boris Johnson’s glib target of India’s Diwali festival in November 2021. They were then delayed last year by general elections in both countries.

First announced in May, the agreement means that tariffs on more than 90% of UK exports to India will be cut over a decade with the largest reductions on cosmetics, clothes and food and drink. Duties on scotch whisky, which make up the bulk of the UK’s current exports, will fall from 150% to 75% immediately and eventually to 40%. In return, 99% of Indian exports to the UK, ranging from gems, textiles, leather and garments to engineering goods, and processed foods, will face zero tariffs.

Tariffs of up to more than 100% on British cars will slide to 10% by 2031, but will be restricted by a quota system till 2046. Negotiations are said to have been extremely tough, with India protecting its motor manufacturing industry. The FT has reported that British car makers are “underwhelmed” but added that government officials said the deal provided “unprecedented liberal access to India’s rapidly growing middle class”.

The deal has not given the UK the access it wants into India’s financial and legal services. Talks are also continuing on a bilateral investment treaty aimed at protecting British and Indian investments in each other’s countries, and on UK plans for a tax on high-carbon industries that India believes could hit its imports unfairly.

This was Modi’s fourth prime ministerial visit to the UK. Following the first one in November 2015, he came in 2018 for a Commonwealth Heads of Government biennial conference, where he played a positive role by helping the Queen ensure that she was succeeded as head of the organisation by Prince, now King, Charles. In 2021, he visited Glasgow for the Cop 26 climate change conference where his policies appeared positive, but India then broke ranks and helped China to water down a resolution phasing out coal-generated electric power.

Modi has been in the UK at a time when India and China are improving their fractured relations, marked with an announcement a few days ago that Chinese tourists could apply f for Indian visas for the first time in five years.

Relations are also improving with archipelago island state of Maldives where Modi stopped for a day on his flight back to Delhi. The current Maldives pro-China government, which was elected 18 months ago on an “India-out” platform, hosted Modi as guest of honour at its 60th independence celebrations yesterday. If this proves to be a real change, it will be a significant gain in India’s attempts to resist China’s development of close relations with all its neighbours.

India’s next target is a trade deal with Trump, who this weekend is at his two golf courses in Scotland where he will meeting Starmer. The US president first announced 26% tariffs on Indian goods on April 2, but postponed that till a new deadline of August 1. India’s trade minister, Piyush Goyal, said in London a couple of days ago that negotiations were making “fantastic progress”. There are however reports that India is testing how the markets would react if a deal is not done by the deadline.

That level of uncertainty no longer exists on the India-UK deal, which will soon challenge both countries to shake off past under-performance and deliver in terms of multi-billion trade and investment.

Posted in India | Tags: China, India, india-and-uk-labour, india-uk-fta, india-uk-trade-deal, modi-chequers, modi-king-charles, modi-sandringham, modi-starmer, news, Pakistan, politics

Phillips exhibition opens to coincide with Lords Test and Wimbledon

Pichwai art sells well and the Ambani family lead at a summer party

South Asian art is on a fresh surge in London with exhibitions and events that build on a boom in sales of Indian modern art. This is being partly fuelled by young high-earning collectors entering the market at a time when India’s financial confidence and markets are strong.

A major selling exhibition of works from across South Asia, Crossing Borders, opened last week at Phillips, a leading UK auction house that is reacting to the market’s potential by focussing on modern Indian and other art from the surrounding countries for the first time.

Partnered with the Grosvenor Gallery, a London-based specialist, there are 150 works by 64 artists priced at £5,000 to £1.5m on show till the end of July. The opening was timed to coincide with last week’s Lords test match (where England narrowly beat India) and the Wimbledon tennis tournament, both of which attract wealthy Indians to London.

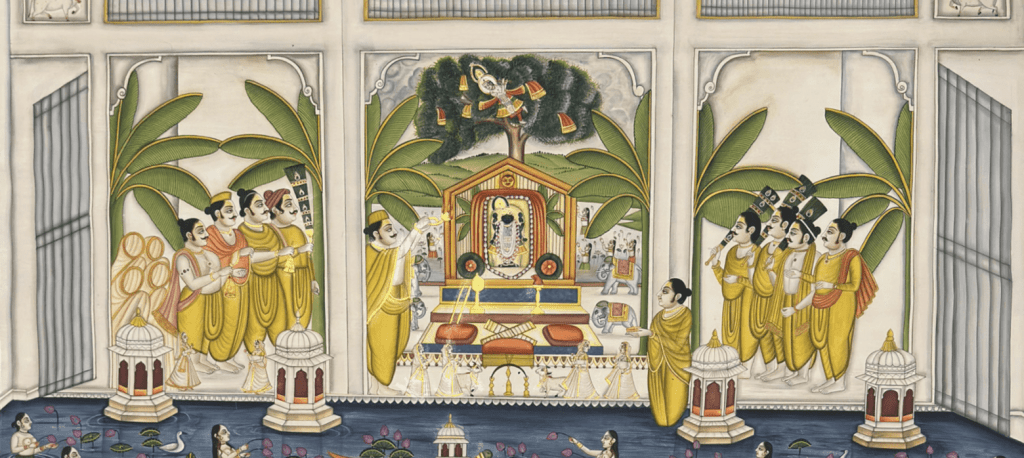

There has also been a splash at the Mall Galleries near Buckingham Palace of some 500 Pichwai paintings on cloth, board and paper produced by local artists in Rajasthan and priced between £95 and £25,000.

This was London’s first major exhibition of the traditional Pichwai art form and was organised by Delhi-based Pooja Singhal, who has been developing a market for some ten years. She says that about 300 works, including the most expensive, were sold in five days, specially attracting Indian buyers among a reported total of some 2,500 visitors.

On a smaller scale but still significant, a cycle rickshaw (below) loaded with stainless steel pots and pans by Subodh Gupta, one of India’s most high-profile contemporary artists, has briefly popped up at the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens, where Indian veteran artist Arpita Singh has an ongoing retrospective exhibition. Gupta also has a small pots installation at the Phillips show.

Furthering the India focus, Isha Ambani Piramal, daughter of Mukesh Ambani, the country’s richest businessman, became the first Indian to lead the host committee for the Serpentine galleries’ glamourous summer party last month. (The annual Serpentine Pavilion has been designed by Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum).

Meanwhile, on a different tack, a painting by Delhi-based artist Mukesh Sharma has been picked by Salman Rushdie for the cover of a new French edition of his 2005 novel Shalimar le clown.

Sharma says Rushdie spotted the 2018 acrylic on canvas on social media. Called Revitalising Memories, it was inspired by the Panchatantra (old animal fables) and folk art. (declaration of interest – I own a Mukesh Sharma painting).

Crossing Borders

Spread across two floors at Phillips in Berkley Square, Crossing Borders has allowed the Grosvenor, which has a relatively small gallery near Pall Mall, to dramatically expand its artists’ annual summer exhibition. It also marks the growing trend for galleries and auction houses to co-operate – Grosvenor works with Saffronart, the market leader for Indian art auctions, on the Art Mumbai annual (November) show.

Phillips does not plan to start auctions of South Asian art but will be including more works from the region in its auctions, says director Yassaman Ali, the exhibition’s curator with Grosvenor’s Conor Macklin.

Indian artists dominate including Bhupen Khakhar, Nilima Sheikh, Anish Kapoor, S.H. Raza, F.N. Souza and Ram Kumar, plus M.F. Husain who has the highest price work at £1.5m, having set an unexpected record for modern Indian art of $13.75m at a Christie’s sale in New York four months ago.

Other significant but somewhat lesser known names include Keralan artist Viswanathan (top image above), who had a recent retrospective with 40 works at Sharjah Biennial 16 spanning five decades, and Rekha Rodwittiya whose works (image above) have been described as “strong, politically vigilant feminist”.

Surprisingly Krishen Khanna, the only surviving major artist from the Raza, Souza and Husain mid-20th century Progressives Group, who has just celebrated his 100th birthday, does not have a painting on show, though his famous bandsmen do appear as a group of bronze statues.

The exhibition is a boost for Sri Lankan artists, five of whom have works led by Senaka Senanayake (below) and George Key. Senanayake’s son, Suren, told me that there was a revival of interest both in Sri Lanka and elsewhere. “When I was growing up, people didn’t really talk about art,” he said. “Sri Lankan art was hanging onto the coat tails of India, but now it’s seen as an asset”.

There are 13 artists of Pakistani origin, two still living in Pakistan – Quddus Mirza and Anwar Syed. The others include Huma Bhabha, a Pakistani American sculptor living in the US whose works are also on show till next month at London’s Barbican gallery, and Rasheed Araeen, who lives in London and had a display of his brightly coloured lattice-construction cubes at the Tate Modern two years ago.

Among other Pakistani artists, there is Abdur Rahman Chughtai, famous for his small finely tuned drawings and paintings that adapt Mughal miniature style with modernism, and Syed Sadequain, who mixed calligraphy and figurative works.

Pichwais, the Mountbattens and beyond

The profile of Pichwai art was raised in the UK 80 years ago by David Hicks, a prominent interior decorator who was married to Pamela Mountbatten, daughter of Lord Mountbatten, Britain’s last Viceroy. Hicks included Pichwais in arts and crafts he brought back for London’s high society.

Originally, the hand-painted tapestries hung as backdrops in shrines behind the statues of Lord Krishna. From that, they have developed for use in various Hindu rituals and festivals depicting sacred cows and other images, but in recent years the works have been little noticed outside India. They are however now beginning at attract attention along with other regional and traditional works, such as Gond tribal art from Madhya Pradesh, as collectors begin to broaden their focus from the modern artists on show at Phillips.

Among prominent buyers are the Ambani family that are credited with giving a significant boost to the artists, acquiring gifts for guests at recent family weddings. They also have a collection that includes a 56-foot-tall Pichwai painting. Titled Kamal Kunj (2019–20), it is the work of Raghunandan Sharma, a leading artist, and Nathdwara illustrators, and is on show at the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre in Mumbai.

Pooja Singhal, who comes from the third generation of a business family that runs a large agrochemicals group (PI Industries), achieved a pr coup for her Pichwai show at the Mall Galleries. Coinciding with the launch, the Financial Times ran a full-page illustrated profile on her Delhi home titled Cultural patron Pooja Singhal: ‘I want to make Pichwai a household name’ in its House & Home section on July 5 (July 3 online). Sponsors of evening events included Conde Nast and India’s Rajasthan-based RAAS hotel group.

Singhal began to develop a business interest in the art form around 2016 and now runs Prichvai Tradition and Beyond which has had exhibitions in various Indian cities including a big presence at the annual India Art Fair in New Delhi.

She was brought up near the Rajasthan city of Udaipur and says she remembers visiting the temple town of Nathdwara, about 40 kms away, where traditional Pichwai textile paintings began 400 years ago as a devotional art form.

Somewhat controversially, Singhal does not have artists’ names on the paintings, nor on authentication certificates. Some sellers however do name their leading artists, for example Artisera, a Bangalore-based art centre,. and the providers of the best in the Ambani collection.

“We work as a collective and no one artist does the work,” she says, explaining that there is no central atelier for what she calls Atelier Tradition and Beyond (ATB), and that the artists are in various locations in and around Jaipur and Udaipur. “Many modern interpretations are conceived by me, or put on paper by a craftsman, and three or four artists complete the composition”. She says that there will be another Pichwai showing at Sotheby’s during London’s Asian Art Week in November.

The biggest event later this year will be a major Royal Academy exhibition at the end of October of works by Indian sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949-2015) and other artists who worked with her. Titled A Story of South Asian Art – Mrinalini Mukherjee and Her Circle, it will be followed by a full Mukherjee retrospective in 2026 at the Hepworth gallery in Wakefield, Yorkshire.

As Salima Hashmi, a veteran Pakistani artist and professor based in Lahore, told me in April when she curated a (not for sale) South Asian exhibition at SOAS, “We come back to the old colonial capital to talk to one another”.

Posted in India, Indian classical art, Indian modern art | Tags: arpita-singh, art, Grosvenor Gallery, India, mountbatten-pichwais, Mrinalini Mukherjee, painting, Phillips Grosvenor, Phillips Indian art, phillips-gallery, phillips-india-plans, Pichwai Mall Galleris, Pichwai Sotheby's, pichwai-paintings, Pooja Singhal artists, Pooja Singhal atelier, Pooja Singhal Pichwai, pooja-singhal, serpentine-gallery

Stephen Cox’s works with an India focus on display at Houghton Hall and in London

Inspiration from goddesses, catamarans and the Concorde jet

When British sculptor Stephen Cox first visited the south Indian town of Mamallapuram that is famous for its ancient stone temples, he “sensed the importance of spirituality in the practices of the local craftsmen who were making sacred Hindu idols, architecture and other devotional objects”.

“Stone is the beginning of everything,” he says. “What enthrals me in Mamallapuram is that you see monolithic boulders that have been converted into shrines and temples as well as evidence of the technique of excavating into the cliffs of granite that reveal deities in the living rock”.

Cox was there during the festival of Ayudha Puja that worships the tools of creation and production and seeks the protection of the Hindu goddess Saraswathi. “Even the smallest tools from humble steel chisels to the forge, trolleys, hammers and the trusty tractor were given the rights of puja,” he says, describing the ceremonies at the local government school of sculpture and architecture near where he later worked.

This included “pouring oil over sculptures to provide religious impulse to their creation”. There was a “total and intense acknowledgement of the tools in the Vaastu tradition” of merging structural design and space.

That was 40 years ago. It drew Cox, as a sculptor, to the mythologies of ancient religions, and has led this summer to a large retrospective exhibition titled Myth at Houghton Hall, an 18th century stately home in Norfolk that is open till the end of September. Built in the 1720s for Sir Robert Walpole, then Britain’s prime minister it is now the seat of his direct descendent David, the 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley.

Cox’s s sculptures, including small bronze works, are also on show at the Grosvenor Gallery in London’s Mayfair till the end of this month (June).

When I talked to him at the Houghton Hall opening, I realised the strong Indian involvement in the inspiration for the sculptures, as well as the stone that he used.

Mostly small delicately shaped works blend in the Houghhton mansion’s grand 18th century rooms with the original décor and ornaments. Indian connections include three “dark torsos” in black basalt. There are also a Bidri Jug and Bottle with a black patinated and copper casing inlaid with sterling silver, the bottle standing on the desk of Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General (right). Cox produced them using Karnataka’s traditional bidri metal handicraft in collaboration with the KASH Foundation in Bangalore, which links artists with traditional craftsmen.

Outside, located on spacious lawns and hidden in woods, are 20 mostly large abstracts and statues with stone from Egypt as well as India along with other sculptures that are permanently there.

The works from Mamallapuram (also known as Mahabalipuram) show Cox’s sense of ancient Hindu mythology.

One of the most accessible and famous comprises a circle of 11 Yoginis (below) , sensuous female deities with human form and animal heads, carved in dark grey basalt, located in a clearing in one of the woods. Part of a series of 64 statues, they are based on Yoginis originally commissioned for 64 circular temples by a ruler during the south Indian Pallavi late 9th and mid-10th century AD dynasty. This became a discredite cult and led to temples being stripped of their most beautiful sculptures, says Cox.

Author and historian William Dalrymple writes in an essay in the exhibition’s expansively illustrated handbook: “In ancient India, yoginis were understood to be the terrifying embodiment of feminine shakti, beautiful, sensual yet fanged beings who feasted on human blood and possessed extraordinary yogic and tantric powers”.

Cox says that he considered there was some room for him as a sculptor “to return to a visual play on the theme of Yoginis looking for animals” like the rhinoceros and the gharial that were not represented in the cult. “With all the sensuality in Indian art there is also a ruthless violence that is represented, but usually in the function of protection and good. There is a very strong nature theme in the cult which may have good possibilities for this age of Global warning”.

Age 79, Cox trained at UK art colleges in the 1960s and is best known for his often-large monolithic sculptures in stone, with site-specific pieces initially in Italy and then in India and Egypt.

His went to India when he was invited in 1985 by the British Council to go to Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu to represent Britain at the Sixth Indian Triennale, where he won a gold medal for his rock cut Holy Family group. He was chosen because he was willing to move there to work, not just visit. Initially he stayed for about six months and set up a workshop, which he still maintains with stpathies, the local craftsmen.

He draws on “indigenous materials to create contemporary works that resonate with historical and cultural connotations,” says the Royal Academy where he is a member. “Using traditional techniques, he has carved marble, alabaster and porphyry rock, and was the first artist for many centuries to gain access to the Imperial Porphyry Quarries in the Eastern Mountains of Egypt”.

His affection for the Tamil Nadu coastal people and traditions is demonstrated by Yatra (above), also called Granite Catamarans on a Granite Wave. First done in the mid-1990s at the Jamali Kamali Gardens near Delhi’s Qutub Munar (left) and now on show at Houghton, fishing boats are balanced on poles in black and white Indian granite.

“I saw the coming and going of fishermen in their catamaran boats setting off like empty hands in the morning and returning with the sea’s bounty in the evening,” says Cox. “The Tamil word catamaran (Catu Maram) means bound logs and its stark simplicity of form reminded me of the supersonic passenger jet Concord that was built in my home city of Bristol”.

He was “struck by the vast difference between the two technologies” and thought that one day he would imagine a way to use the form and commemorate its beauty into a sculpture, which he eventually did. That happened after the 2004 tsunami hit the coast and led to the boats being modernised with fibre glass and resin, helped by South Korea. “With the white diorite posts that marched across the landscape of South India I devised a sea upon which the boats could float,” he says

Anthony Gormley, a famous British sculptor, who taught art along with Cox at the start of their careers and had his work on show at Houghton last year, told me at the opening that his favourite sculpture was Interior Space, a 14-tonne sarcophagus or stone coffin first carved in 1995 (above).

“Stephen’s use of the void is very interesting, making emptiness mean something with his use of space,” says Gormley. “You don’t need to go inside,” he laughed, explaining about the temptation to squeeze through a narrow vertical slit that only extremely slim people can do with any confidence they will be able to squeeze out again. Cox’s website more seriously says, “The imaginative conceptions of the ‘afterlife’ of the peoples of ancient civilisations is the driver of the series”.

There’s also a sense of possibly inaccessible or inescapable space in the arrangement of a decorative mass of delicately coloured Aswan granite from Egypt (right) that dominates the view from the main house down a wide swathe of grass that stretches into the distance towards Sandringham, King Charles’ country retreat.

It’s possibly the most instantly appealing work in the grounds and emerged, unexpected, when a large boulder was split into slices and revealed what looked like bodies and ghostly faces. Cox’s sculptor’s role came into play with the void between the slices, accessible through tempting gaps.

“For me,” says Cox, “art is a metaphor for the things that religion, as a domain, actually gives a man – the spiritual”.

Recent Comments