Manmohan Singh, who died on December 26 at the age of 92, was prime minister of India from 2004 to 2014, but he will be best remembered for launching economic reforms in 1991, paving the way for the emergence of today’s expanding and internationally significant economy.

Primary credit for that dramatic political move should go to Narasimha Rao, who had become prime minister after a general election in the middle of a deep financial crisis. Rao appointed Singh to be his finance minister with a brief to dismantle India’s protectionism and isolation, unpicking what was known as the state capitalist-based economy’s “license raj” and releasing the private sector to expand.

Respected as an economist, Singh had written about the problems in India’s Export Trends, his doctoral thesis published in 1964. He then realised how far India was slipping behind Southeast Asia’s emerging markets (because of leftist policies that he had helped implementing), when he spent three years from 1987 as secretary general of the development-oriented South Commission in Geneva.

Reformer

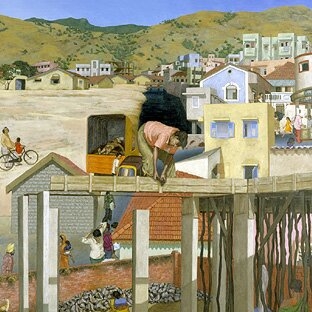

That made him a committed reformer. After devaluing the rupee in 1991, he quickly adopted and expanded plans already developed by top officials, dismantling decades of economic restrictions, liberalising trade, and introducing fiscal discipline.

These changes energised economic growth, encouraged the beginnings of integration with the global economy, and began the emergence of India as a significant player in international markets. But Rao’s enthusiasm for reforms waned after Congress suffered state assembly election losses in December 1994, and Singh lacked the political stamina to fight for more reforms.

Singh’s contributions to modern India continued in 2004 when, aged 71, he was chosen to be prime minister by Sonia Gandhi, leader of the Indian National Congress and its United Progressive Alliance coalition that had just won a surprise general election victory. Gandhi did not want the job and Singh had for some time been mooted in the media as a possible prime minister. For dynasty-conscious Gandhi, he was a safe unambitious bridge between her late husband Rajiv, who had been prime minister in the 1980s and was assassinated in 1991, and their son Rahul.

A book written by Singh’s media adviser, Sanjaya Baru, was titled The Accidental Prime Minister. The question that will always be asked is whether it would have been better if, after decades as a bureaucrat, leading economist and finance minister respected for his integrity and visible humility, he had retired to a distinguished public life away from government instead of accepting the prime ministership with limited authority.

Singh had a successful first five years as prime minister and built a strong international reputation, but in his second term from 2009 he became increasingly isolated looking, say observers, weak and lost. There were suggestions in 2012 that Pranab Mukherjee, then the finance minister, should become prime minister with Singh becoming president, but Sonia Gandhi would not agree because, for historic reasons, she did not trust Mukherjee.

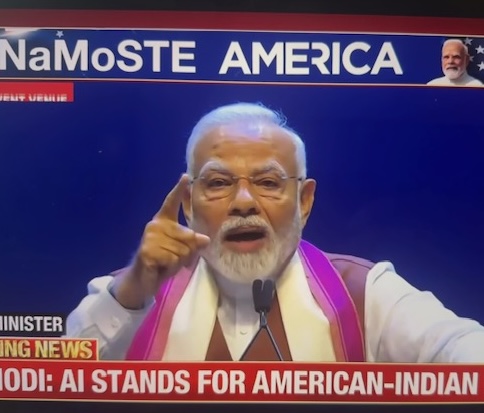

Singh therefore remained prime minister without the power to control the corrupt and ineffective government. This paved the way for Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party to sweep to victory in 2014 and pick up, with fresh energy and determination, initiatives that Singh had begun.

Singh has said that his “best moment” was signing a civil nuclear deal with the U.S. in 2008 during his first term after overcoming setbacks and considerable opposition with rarely seen political skill. This opened the way for India to access nuclear fuel and technology from abroad, though no US reactors have been built because of various issues including accident liability. More importantly, it paved the way for defence and other co-operation, which has led to much wider positive transformation in the two countries’ relationship.

That deal, Singh said in his final press conference as prime minister, ended “the nuclear apartheid which had sought to stifle the processes of social and economic change and technical progress of our country in many ways”. He also said his biggest regret was not doing more on healthcare, especially for women and children.

Reforms included legislation on a rural jobs scheme, food security, and the right to information. He also initiated moves on sales tax reform and on a digital identity scheme called Aadhaar that has led to paperless payment systems that specially benefit the poor.

More could have been done had he not been hampered by a lack of backing from Gandhi who remained party leader, along with rebellious (and corrupt) ministers that he did not have the power to dismiss, plus rival Congress politicians who resented his presence and manoeuvred against him.

He was heavily criticised for failing to assert his authority, which led him to say in his last press conference, “I honestly believe history will be kinder to me than the contemporary media or for that matter, the opposition parties in parliament”.

The first member of India’s minority Sikh religious community to become prime minister, Singh was born on September 26, 1932, one of ten children, to a poor family in a Punjab village that is now part of Pakistan. Singh used to recall that his village had no doctor and that he walked miles to go to school before his family migrated to India when Pakistan became a separate, primarily Muslim country at independence in 1947.

Oxbridge

His education took him from Punjab University to the UK where he gained a first in economics at Cambridge University, followed by a doctorate at Oxford in 1962 that led to a book on Indian exports and prospects for growth.

Singh’s government career began in 1971 when he became economic adviser in the commerce ministry followed a year later by a similar but far more important post in the finance ministry.

Later, in the 1980s, he became governor of the Reserve Bank of India and deputy chairman of the Planning Commission. I was then the Financial Time’s South Asia correspondent and valued my interviews with him when he willingly explained India’s problems and what was needed to overcome them.

He was chairman of the University Grants Commission when he was summoned by Narasimha Rao to be finance minister. He was so surprised to get the call, he told the BBC’s Mark Tully, that he didn’t at first take it seriously, delaying his meeting with Rao for a day.

That demonstrates the modesty of a distinguished public servant who is now remembered for his rare integrity and for his contributions to modern India.

Recent Comments