Demands for repeal of reform laws rushed through parliament

Opposition centred mainly on Punjab and also Haryana

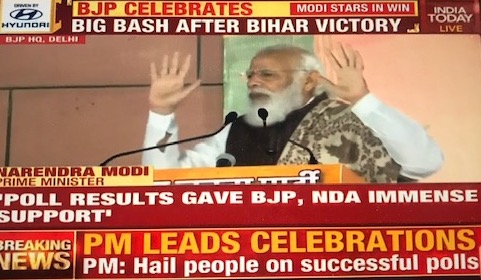

Narendra Modi’s authoritarian rule – supported by his home minister Amit Shah – is facing what look like its biggest challenge since 2014 with thousands of farmers staging more than a week of mass protests, blocking highways on the outskirts of New Delhi, India’s capital. They are demanding the repeal of recent agricultural legislation that introduces reforms affecting the selling and pricing of their crops.

The farmers have refused to be tempted into the city for a controlled demonstration and have stayed where they have most power – on the highways, blocking as many as seven main routes into the capital. Some have joined by wives, widening the base of the protests, along with food canteens and entertainers. They are reported to be in no hurry to go home – seasonal crop harvesting and sowing have just been completed in the state of Punjab that is leading the protest along with neighbouring Haryana.

Shah, uncharacteristically, tried to mediate earlier in the week, but more than three hours of talks with 35 representatives from more than 20 farmers’ organisations failed when they rejected creation of a small committee to examine the issues. Today there have been more than seven hours of talks (the farmers took their own food and refused the government’s) with 40 organisations but no final solution has been found. Talks will be resumed on December 5. [Dec 5: four hours of talks have failed to lead to a breakthrough – more talks Dec 9]

Meanwhile the protests on the highways (right) and elsewhere have been gathering momentum, mostly peaceful after some early clashes with police and paramilitary forces.

The basic demand has been for the government to recall parliament and repeal three laws that it passed last September. That would be a huge climb-down that Modi and Shah clearly want to avoid, so the government is offering ways to ease some of the farmers’ concerns, which might lead to the laws being amended.

The reforms are needed and have been proposed by successive government in varying packages for some 20 years – the Congress Party, which is supporting the current protests, included them in its last general election manifesto.

The aim is to bring agriculture into line with India’s primary reforms that began to open up the economy in 1991. The reforms have been partially implemented in southern states, but there has been repeated opposition in the north because of the sensitivities of India’s hundreds of millions of farmers, many with tiny holdings, and because of vested interests ranging from large farmers to government market agents.

The BJP government cannot be blamed for what it is trying to do. Indeed it should be praised for trying to solve an old problem that has been holding back development of agriculture, which involves half of India’s 1.38bn people.

It can however be blamed for the insensitive way that it issued executive orders in June and then rushed approval of the three bills through parliament in September as part of a Covid-19 reform package when hearings were encumbered by the pandemic shutdown. Modi and Shah ignored calls for the usual detailed consideration and debate, assuming that they would not face significant opposition.

The issues are emotive but the protests so far have been primarily party political, driven by Punjab which has a Congress state government. The state’s highways and railways (below) were blocked from September by members of 31 organisations representing nearly one million farmers before the protests spread to Delhi

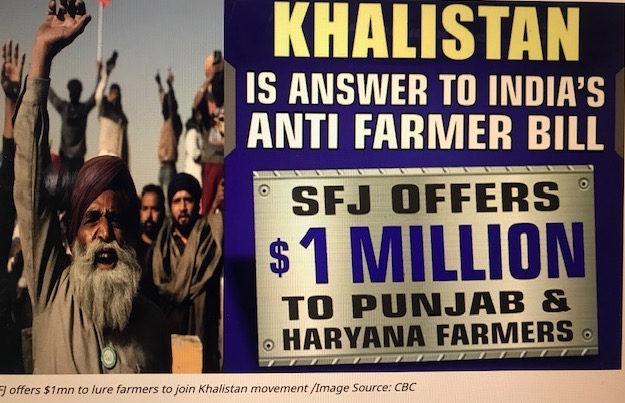

Khalistan

Modi seems to have not realised that Punjab has proud characteristics that differentiate it from other states and that affect how it should be handled. It is the home of the Sikh religion and, as Shekhar Gupta, a leading editor pointed out in ThePrint.in last week, it “is not part of the Hindi/Hindu heartland” that instinctively backs Modi. Sikhs do not subscribe to the nationalist Hindutva.

It had the bloody Khalistan independence movement in the 1980s, which was wiped out as a terrorist force at the beginning of the 1990s, but still has some appeal.

Khalistan’s banned Sikhs for Justice (SFJ) banners have been seen (left) on the highway protests . The government should therefore be taking care to ensure that the current protests do not result in a revival of social unrest among the youth – earlier generations provided the foot soldiers for the Khalistan movement.

The state has a youth unemployment rate of 26% and farmers fear they are losing their identity and ability to act as a political force. The youth have not till now had “a focal point around which to coalesce their grievances,” Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a prominent political scientist, wrote in the Indian Express. This “might be sustaining the farmers’ agitation and driving it to a greater show of strength”.

The idea behind the legislation is to remove restrictions on the sale of produce so that farmers can avoid bureaucratic and often corrupt mandis (local public sector markets) that have a statutory monopoly in many, but not all, states. This should boost both food processing, which currently only absorbs 10% of production, and exports that only account for 2.3% of world trade.

“These reforms have not only broken shackles of farmers but have also given new rights and opportunities to them,” Modi claimed last week in his Mann Ki Baat (monthly radio talk).

Under India’s complex quasi-federal constitution, agriculture is a state subject but the central government also has powers, which it used for the September legislation. Two of the bills allowed farmers to bypass state-mandated mandis and sell to whomever they like, and provided a structure for contract farming with direct farmer-to-buyer deals. The third bill lowered government control on production, sale and distribution of key commodities.

Individual states have the right to reject or amend new laws, which some have done. In Punjab and Haryana, however, the states’ governors have not approved amended laws, presumably on instructions from the central government.

The farmers’ unions are now complaining that they were not consulted. They are understandably concerned that private sector buyers will deal with them more harshly than the current mandis where influence can be peddled, and relationships developed between the farmer and commission agents who often become family moneylenders.

They are also concerned that they will lose the protection of food grains’ minimum support prices that guarantees prices the government pays – in Punjab and Haryana, the government’s Food Corporation of India buys 85% of the main wheat and paddy. Modi has publicly stated several times that the support price system will not be removed, but the fear remains. The farmers’ organisations want this enshrined in law, which the government does not want to do, but it seems that ministers are discussing ways to spread the minimum price protection to private sector deals.

Modi has often been criticised for his poor execution of policies. This time it is his hubris and insensitivity that has opened the way for the issue to be politicised by the opposition and vested interests.

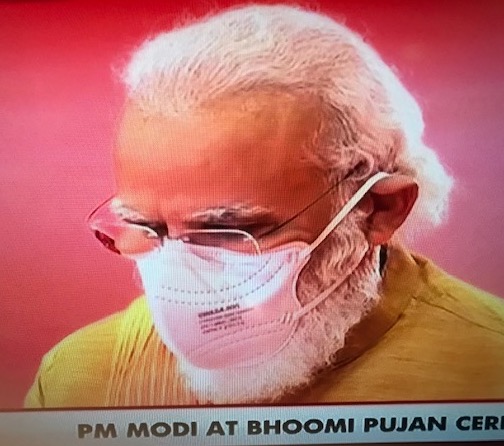

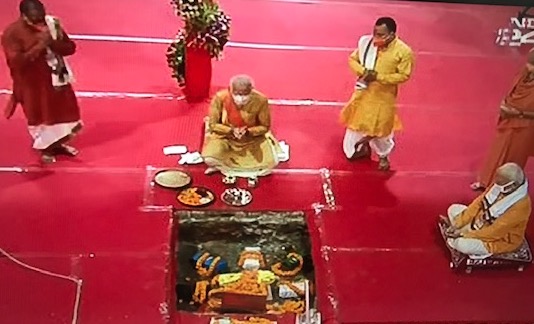

He was the central figure of the ceremony, establishing Hinduism’s historical role and its dominance at the expense of other religions, notably Islam.

He was the central figure of the ceremony, establishing Hinduism’s historical role and its dominance at the expense of other religions, notably Islam.

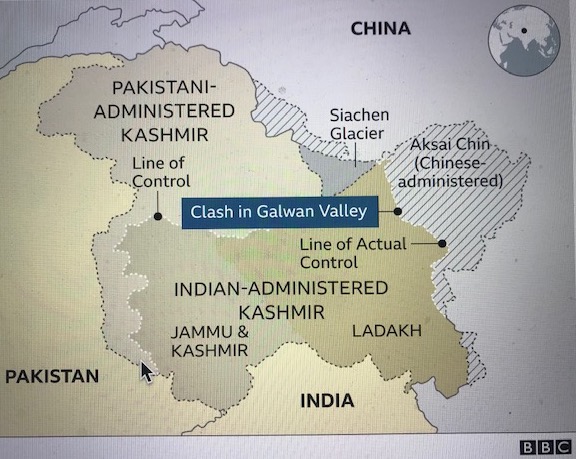

This was not a war situation between the two nuclear powers, nor were shots fired, but urgent diplomatic and military talks have been held between the two sides in an attempt to avoid further conflict.

This was not a war situation between the two nuclear powers, nor were shots fired, but urgent diplomatic and military talks have been held between the two sides in an attempt to avoid further conflict.

Recent Comments